Introduction

What is camel milk?

Nutrient profile

Digestibility and tolerance

Antioxidant and immune-supporting components

Potential metabolic effects

Therapeutic claims and evidence

Camel milk vs. other milks

Limitations and research gaps

Practical use and considerations

Conclusions

References

Further reading

Camel milk is a nutrient-dense dairy alternative with distinct protein composition, bioactive compounds, and potential metabolic and immune-supporting properties. Current evidence suggests benefits for digestibility and glucose regulation, while emphasizing the need for larger, standardized clinical trials to confirm therapeutic effects.

Image Credit: Maarten Zeehandelaar / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: Maarten Zeehandelaar / Shutterstock.com

Introduction

Historically, camel milk provided sustenance and supported nutritional needs, food security, and health practices to communities throughout the Middle East, Africa, and parts of Asia. Scientific research increasingly highlights the potential therapeutic properties of camel milk, some of which include antimicrobial, antioxidant, antidiabetic, and anti-inflammatory effects, positioning camel milk as both a traditional food and emerging functional dairy product.1

This article discusses the traditional use of camel milk while exploring its digestibility, potential metabolic and immune-enhancing effects, and key research gaps for informed dietary use.

What is camel milk?

Camel milk is obtained from dromedary (one-humped) and Bactrian (two-humped) camels across the Middle East, East and Central Africa, and parts of Central Asia. Camel milk differs from cow’s milk in sensory and biochemical characteristics, including a slightly salty taste and notable variation in protein fractions, fat globule structure, and lactose concentration.2,3

Nutrient profile

Camel milk is a source of high-quality protein and essential amino acids that support tissue repair and metabolic function. It provides key micronutrients including calcium, potassium, zinc, and iron, and contains vitamin C at concentrations approximately three to five times higher than cow’s milk, which is particularly valuable in arid regions with limited access to fresh produce.1,3

Camel milk contains several bioactive proteins, including lactoferrin, immunoglobulins, lysozyme, and antioxidant peptides, which contribute to immune modulation and antimicrobial activity.1,4

Digestibility and tolerance

The protein composition of camel milk differs from that of cow’s milk, as it lacks β-lactoglobulin and contains lower levels of αs1-casein, proteins commonly associated with milk allergy and intolerance. These structural differences result in softer curd formation during gastric digestion, facilitating faster gastric emptying and protein hydrolysis.2,4

Camel milk generally contains lower and more variable lactose levels (approximately 2–6%) compared with cow’s milk, which may improve tolerance in some individuals with lactose sensitivity.1,4 Reduced lactose content may also result in lower formation of bioactive casomorphins, which can slow intestinal motility.5

Why Camel Milk Is So Expensive | So Expensive

Antioxidant and immune-supporting components

Camel milk contains bioactive peptides, vitamins, and trace minerals that contribute to antioxidant defense by reducing oxidative stress. Whey proteins such as lactoferrin and lysozyme exhibit antimicrobial and iron-chelating properties that may limit pathogen growth, along with angiotensin-I-converting enzyme (ACE)-inhibitory peptides that may support vascular and metabolic health .1,4,5

Camel milk immunoglobulins, primarily IgG, are structurally smaller than those in bovine milk and may enhance intestinal absorption and immune signaling. Lactoferrin further contributes to immune regulation through anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial pathways.1,4

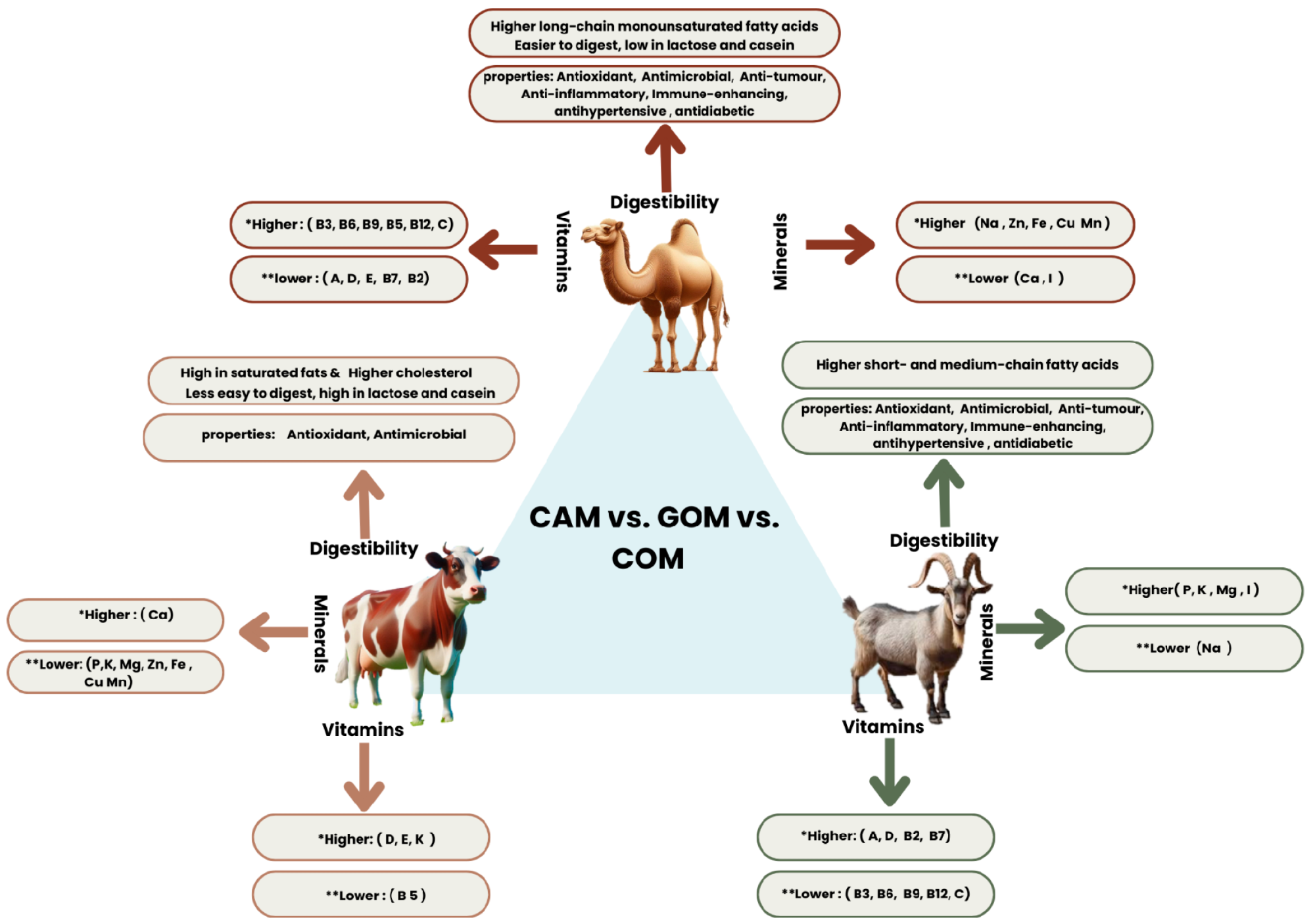

Comparison between camel, goat, and cow milk based on digestibility, minerals, and vitamins. CAM: camel milk; GOM: goat milk; and COM: cow milk. * Higher compared to the other two milk types, it has the highest content. ** Lower compared to the other two milk types, it has the lowest content. Ca, calcium; Fe, iron; P, phosphorus; K, potassium; Mg, magnesium; Cu, copper; Mn, manganese; Zn, zinc; Na, sodium; I, iodine; vitamin D, calciferol; vitamin A, retinol, or retinoic acid; vitamin B2, riboflavin; vitamin B3, niacin (or nicotinic acid); vitamin B12, cobalamin; vitamin B5, pantothenic acid; vitamin B9, folate (or folic acid); and vitamin B7, biotin.5

Experimental studies and small clinical trials report improvements in fasting blood glucose, insulin sensitivity, and lipid metabolism in individuals consuming camel milk. These effects are associated with the presence of insulin-like proteins and bioactive peptides that appear resistant to gastric degradation and may influence insulin signaling pathways.4,6

Some studies also indicate modest reductions in total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein levels. However, current evidence remains preliminary, and findings vary depending on study design, population, and duration of intake.4,6

Therapeutic claims and evidence

Animal models and small human clinical trials suggest that camel milk consumption may reduce fasting glucose, glycated hemoglobin, and exogenous insulin requirements, particularly in individuals with type 1 diabetes. In most clinical studies, these effects were observed with daily intakes of approximately 500 mL of fresh camel milk consumed over several months , and are frequently attributed to insulin-like proteins and antioxidant components that may enhance glucose utilization.6

Despite promising findings, heterogeneity in study size, intervention length, and outcome measures limits definitive clinical conclusions. Larger randomized controlled trials using standardized protocols are required to clarify therapeutic efficacy and safety.6

Camel milk vs. other milks

Compared with cow and goat milk, camel milk contains lower lactose levels, higher vitamin C and iron content, and a distinct protein profile lacking β-lactoglobulin. Camel milk also contains bioactive peptides and insulin-like proteins that are absent or present at lower concentrations in other milks.4,5

Goat milk is often considered more digestible than cow milk; however, camel milk exhibits a broader range of antimicrobial and metabolic bioactivities. Nonetheless, camel milk’s strong flavor, limited availability, and higher cost affect consumer acceptance and market expansion.5

Image Credit: photos_adil / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: photos_adil / Shutterstock.com

Limitations and research gaps

Most camel milk research is based on laboratory studies, animal models, or short-term human trials. Evidence on processed forms such as powdered camel milk remains especially limited, with few studies evaluating long-term nutritional or metabolic outcomes.1,7

Well-designed multicenter clinical trials with standardized processing methods, dosages, and outcome measures are needed to strengthen dietary and therapeutic recommendations.1,7

Practical use and considerations

Camel milk is commercially available in several forms, including fresh liquid milk, powdered formulations, and a limited range of specialty products. Sensory studies indicate that although fresh camel milk is generally preferred, powdered camel milk demonstrates acceptable taste and comparable willingness to pay, offering potential advantages in shelf life and distribution where cold chains are limited.7

Despite its notable nutritional and bioactive properties, camel milk should be incorporated as part of a balanced and varied diet, rather than as a standalone therapeutic intervention. Practical adoption may be limited for many consumers due to its distinct taste, which differs from that of cow’s milk, as well as challenges related to cost, supply chains, and accessibility outside traditional camel-rearing regions.1

Conclusions

Emerging data indicate that camel milk may help regulate metabolic processes, aid digestion, and improve immune function, particularly among individuals with lactose intolerance or metabolic disorders. As a nutrient-dense food containing bioactive compounds, camel milk represents a promising alternative dairy source. However, broader clinical validation is required before firm therapeutic recommendations can be made.

References

- Swelum, A. A., El-Saadony, M. T., Abdo, M., et al. (2021). Nutritional, antimicrobial and medicinal properties of Camel’s milk: A review. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences 28(5). 3126-3136. DOI: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2021.02.057. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1319562X21001285

- Ho, T. M., Zou, Z., & Bansal, N. (2022). Camel milk: A review of its nutritional value, heat stability, and potential food products. Food Research International 153. DOI: 10.1016/j.foodres.2021.110870. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0963996921007705

- Singh, S., Mann, S., Kalsi, R., et al. (2024). Exploring the therapeutic and nutritional potential of camel milk: challenges and prospects: a comprehensive review. Applied Food Research 4(2). DOI: 10.1016/j.afres.2024.100622. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2772502224002324

- Muthukumaran, M. S., Mudgil, P., Baba, W. N., et al. (2023). A comprehensive review on health benefits, nutritional composition and processed products of camel milk. Food Reviews International 39(6). 3080-3116. DOI: 10.1080/87559129.2021.2008953 https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/87559129.2021.2008953

- Almasri, R. S., Bedir, A. S., Ranneh, Y. K., et al. (2024). Benefits of Camel Milk over Cow and Goat Milk for Infant and Adult Health in Fighting Chronic Diseases: A Review. Nutrients 16(22). DOI: 10.3390/nu16223848. https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/16/22/3848

- Mirmiran, P., Ejtahed, H. S., Angoorani, P., et al. (2017). Camel milk has beneficial effects on diabetes mellitus: A systematic review. International Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism 15(2). DOI: 10.5812/ijem.42150. https://brieflands.com/journals/ijem/articles/13693

- Ibrahim, A. M., Ali, S. M., Osman, Y. M., et al. (2025). Sensory trial of camel milk powder among pastoralist communities of the Somali Region, Ethiopia. PLoS One 20(10). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0333358. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0333358

Further Reading

Last Updated: Jan 26, 2026