Why mismatched resistance thresholds between CLSI and EUCAST could be masking the true scale of antimicrobial resistance in the environment. How can global standardization fix this problem?

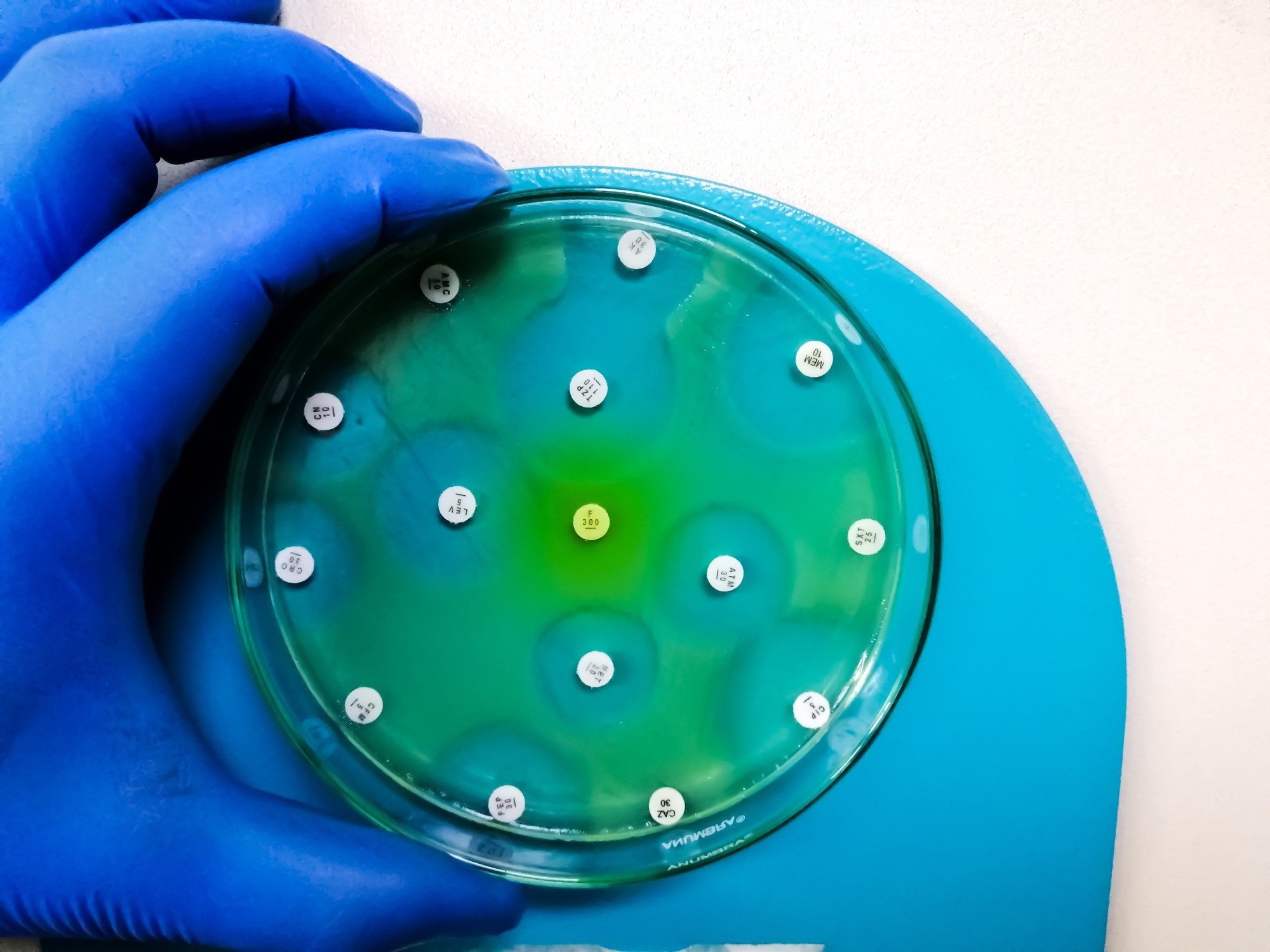

Study: Antimicrobial resistance surveillance in the natural environment: standardization of minimum inhibitory concentration breakpoint. Image credit: Arif biswas/Shutterstock.com

Study: Antimicrobial resistance surveillance in the natural environment: standardization of minimum inhibitory concentration breakpoint. Image credit: Arif biswas/Shutterstock.com

In a recent review published in the journal New Contaminants, a group of authors reviewed current antimicrobial resistance (AMR) surveillance approaches and argued for an urgent global need for greater standardization of minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) breakpoints, warning that inconsistent interpretation can undermine both environmental monitoring and clinical decision-making.

Background

Antibiotics were transformative for modern medicine, but their effectiveness is increasingly undermined by rising resistance. As reported in 2019, an estimated 4.95 million deaths were associated with AMR worldwide, and now antibiotics are commonly found in soil, rivers, and even groundwater. Here, dangerous resistant bacteria can grow, and environmental reservoirs of resistance can contribute to their spread across ecosystems, communities, and healthcare settings.

Monitoring this growing threat depends on reliable surveillance tools, but inconsistent measurements prevent global comparisons. Without standardized benchmarks, resistance trends can be misinterpreted, delaying action and weakening public health responses. The review highlights the need for harmonized resistance assessment frameworks across regions to ensure resistance data are comparable and actionable.

What is AMR in the environment and why it matters?

AMR has spread beyond hospitals, as residues of antibiotics used in agriculture, healthcare, and livestock leak into the environment and accumulate in water and soil. Even in small amounts, these residues can help antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB) grow and promote the development of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs). Once these ARGs emerge, bacteria can exchange resistance traits through horizontal gene transfer, accelerating the spread of resistance.

Environmental resistance poses a direct risk to human health because it does not remain confined to natural settings. Resistant bacteria from water, food, or soil can reach humans and make common infections harder to treat. Rising resistance increases treatment failure, hospital stays, and healthcare costs. This makes tracking environmental resistance critical for global health security.

Surveillance strategies for AMR

Presently, AMR surveillance methods are commonly grouped into genetic-based approaches and phenotypic approaches, with phenotypic tools further divided into conventional and emerging methods that differ in speed, cost, and interpretive power.

Genetic-based detection methods

Genetic techniques detect antibiotic resistance by identifying specific genes in bacteria. Methods such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR), quantitative PCR (qPCR), deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) microarrays, metagenomic sequencing, and clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats with CRISPR-associated proteins (CRISPR-Cas) are fast and highly sensitive. Targeted PCR-based methods can return results within one to two hours, making them useful for early warning systems and large-scale environmental monitoring.

However, metagenomic sequencing typically requires longer processing times. A key limitation is that the presence of a resistance gene does not always translate into actual resistance. Genetic methods cannot determine whether an antibiotic truly inhibits bacterial growth, nor can they reliably identify novel or unknown resistance mechanisms.

The review also notes that environmental metagenomic datasets may inadvertently include human genetic material, raising ethical and privacy concerns that complicate large-scale data sharing.

Phenotypic methods and the role of Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

Phenotypic methods detect antibiotic resistance by directly observing bacterial growth in the presence of antibiotics. These methods determine the MIC, the lowest antibiotic concentration that inhibits visible bacterial growth. MIC testing is considered the gold standard for antibiotic susceptibility testing because it reflects the real biological response rather than genetic potential alone.

Traditional methods, including disk diffusion, broth microdilution, and the E-test, are widely used. They are affordable and standardized but can be slow and influenced by environmental conditions, bacterial growth rates, and operator variability.

Newer phenotypic methods such as Raman spectroscopy, flow cytometry, microfluidic platforms, and live-cell imaging enable rapid, high-resolution analysis at the single-cell level. While highly promising, their high cost, technical complexity, and specialized expertise requirements currently limit widespread adoption, particularly outside advanced laboratories and resource-rich settings.

How MIC breakpoints shape resistance interpretation

MIC values alone cannot determine whether an antibiotic will be effective. They must be interpreted using antimicrobial susceptibility breakpoints, predefined thresholds that classify bacteria as susceptible, intermediate, or resistant. These breakpoints are essential for guiding treatment decisions, analyzing resistance trends, and interpreting surveillance data across clinical and environmental studies.

The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) and the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) are the two dominant authorities defining breakpoints worldwide. Both organizations rely on microbiological data, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic modeling, and clinical outcomes, but their criteria and interpretive frameworks often differ.

Problems of inconsistency between CLSI and EUCAST

CLSI traditionally emphasizes flexibility in treatment decisions, retaining an intermediate category that allows clinicians to adjust dosing strategies. EUCAST, by contrast, places greater emphasis on whether treatment will succeed at recommended or increased antibiotic exposure levels and redefined the I category in 2020 to mean susceptible, increased exposure, while also introducing a technical uncertainty.

These differences have real-world consequences. For example, the review highlights how differing ciprofloxacin breakpoints for Escherichia coli can shift the same isolate from susceptible under one system to resistant under another, potentially leading to different treatment choices depending on geographic location. On a global scale, such inconsistencies distort resistance statistics, complicate comparisons across regions, and hinder accurate tracking of emerging resistance threats in both environmental and clinical datasets.

Why global standardization is urgent

Without standardized testing and interpretation, tracking antibiotic resistance becomes increasingly difficult. Policymakers may underestimate or overestimate resistance levels, leading to misallocated resources, while clinicians may resort to unnecessary use of broad-spectrum antibiotics. In environmental surveillance, inconsistent methodologies make it difficult to link pollution-driven resistance to human health risks.

The review argues that a globally harmonized breakpoint system would allow laboratories to interpret MIC data using a common framework, improving data comparability, treatment decisions, and early detection of resistance trends while strengthening links between environmental monitoring and public health action.

Conclusions

AMR surveillance depends on accurate measurement and consistent interpretation. While advances in genetic and phenotypic technologies have improved detection capabilities, MIC-based testing remains central to resistance assessment. However, differences between breakpoint systems used by major authorities weaken both global surveillance efforts and clinical decision-making.

The authors conclude that international collaboration, harmonized breakpoint criteria, affordable monitoring tools, and emerging approaches such as artificial intelligence will be essential to slow the spread of AMR and protect public and environmental health in the face of accelerating resistance pressures.

Download your PDF copy now!

Journal reference:

-

Tang, M., Wang, Z., Zhu, H., Ma, N. L., Yang, Z., Tian, Y., & Li, H. (2026). Antimicrobial resistance surveillance in the natural environment: standardization of minimum inhibitory concentration breakpoint. New Contaminants. 2. DOI: 10.48130/newcontam-0025-0023. https://www.maxapress.com/article/doi/10.48130/newcontam-0025-0023