Introduction

What are edible insects?

Nutrient density and macronutrient profile

Vitamins and minerals

Protein quality and digestibility

Fatty acids and lipids

Fiber, chitin, and digestive health

Sustainability and nutritional implications

Allergenicity and safety considerations

References

Further reading

Edible insects provide nutrient-dense proteins, beneficial lipids, essential micronutrients, and dietary fiber, with nutritional profiles shaped by species, life stage, processing, and rearing substrates. Current evidence, largely based on compositional analyses, supports their potential role in sustainable food systems while highlighting the need for standardized production, safety oversight, and long-term human studies.

Image Credit: Korawat photo shoot / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: Korawat photo shoot / Shutterstock.com

Introduction

Edible insects like caterpillars, termites, crickets, beetles, and other species have been historically consumed in traditional diets throughout Africa, Asia, and Latin America. More recently, nutrition science and food-security research have investigated the potential of insects as viable alternative proteins that simultaneously provide diverse essential nutrients, efficient feed conversion, and comparatively low environmental footprints.

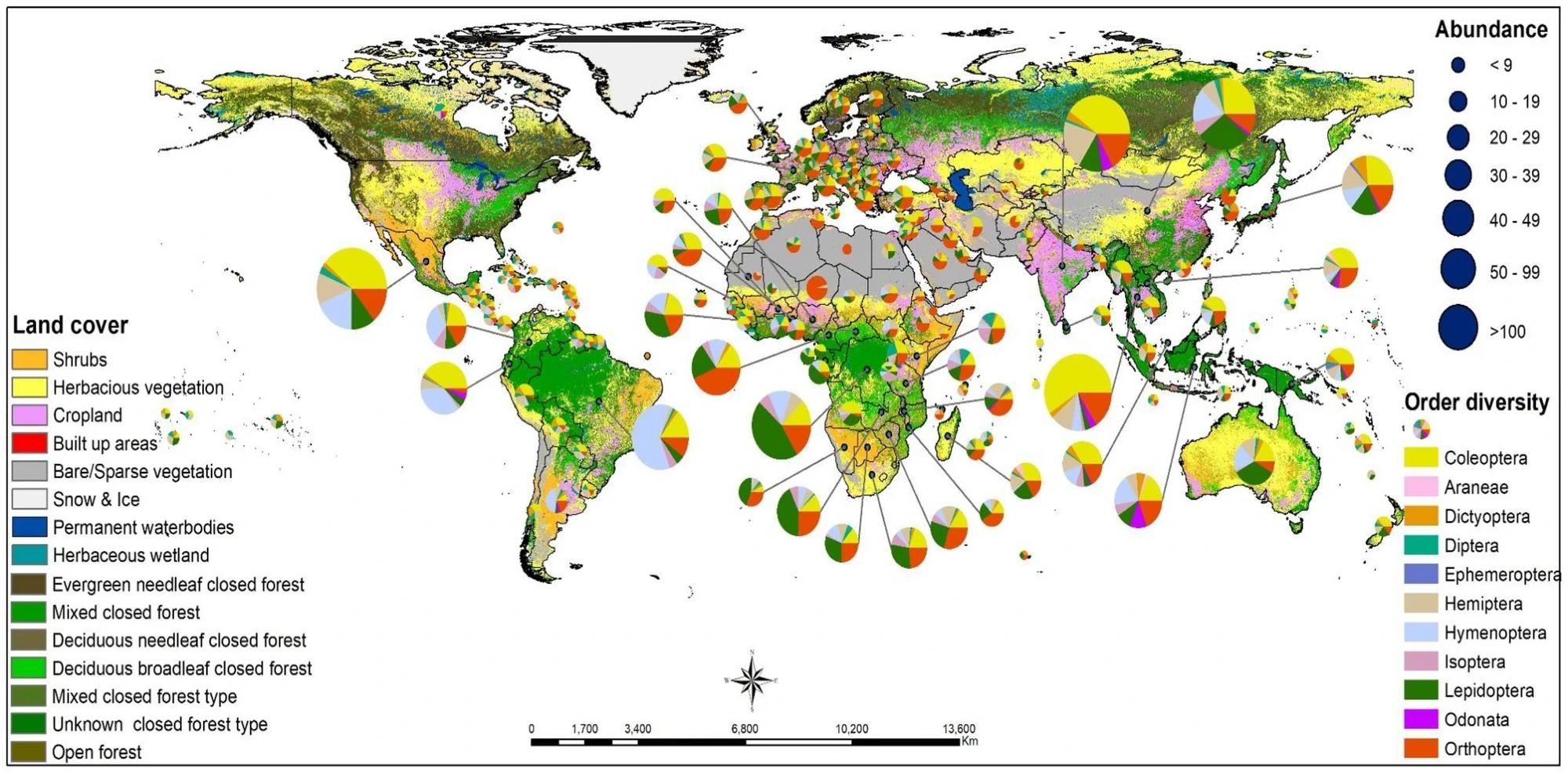

Large-scale global inventories and biodiversity analyses indicate that approximately 2,200–2,300 edible insect species are consumed across 128 countries, with the highest species diversity reported in Asia, followed by Mexico and several Central and Sub-Saharan African nations1. Most existing evidence on nutritional value is derived from compositional analyses and short-term studies rather than long-term human dietary interventions. With rapid climate change and resource constraints, edible insects are increasingly being reconsidered as scalable, sustainable ingredients for both human and animal consumption.

Global distribution of potentially edible insect species across different land cover classifications. Potentially edible insect species imply both confirmed and unconfirmed edible insects. The figure was generated using QGIS geographic information system software version 3.34.3 (http://qgis.osgeo.org/).1

What are edible insects?

Edible insects range from crickets (Acheta domesticus), mealworms (Tenebrio molitor), and grasshoppers to beetle larvae, ants, termites, and silkworm pupae. Edible insects can be consumed either as whole after being fried, roasted, or boiled, or processed into powders, pastes, and oils for breads, pasta, snacks, and protein bars.

In Western markets, insect-derived ingredients are most commonly incorporated into familiar food matrices (such as flours or protein isolates) to reduce neophobia while improving protein and micronutrient density. This approach aligns with evolving sustainability and nutrition goals.2

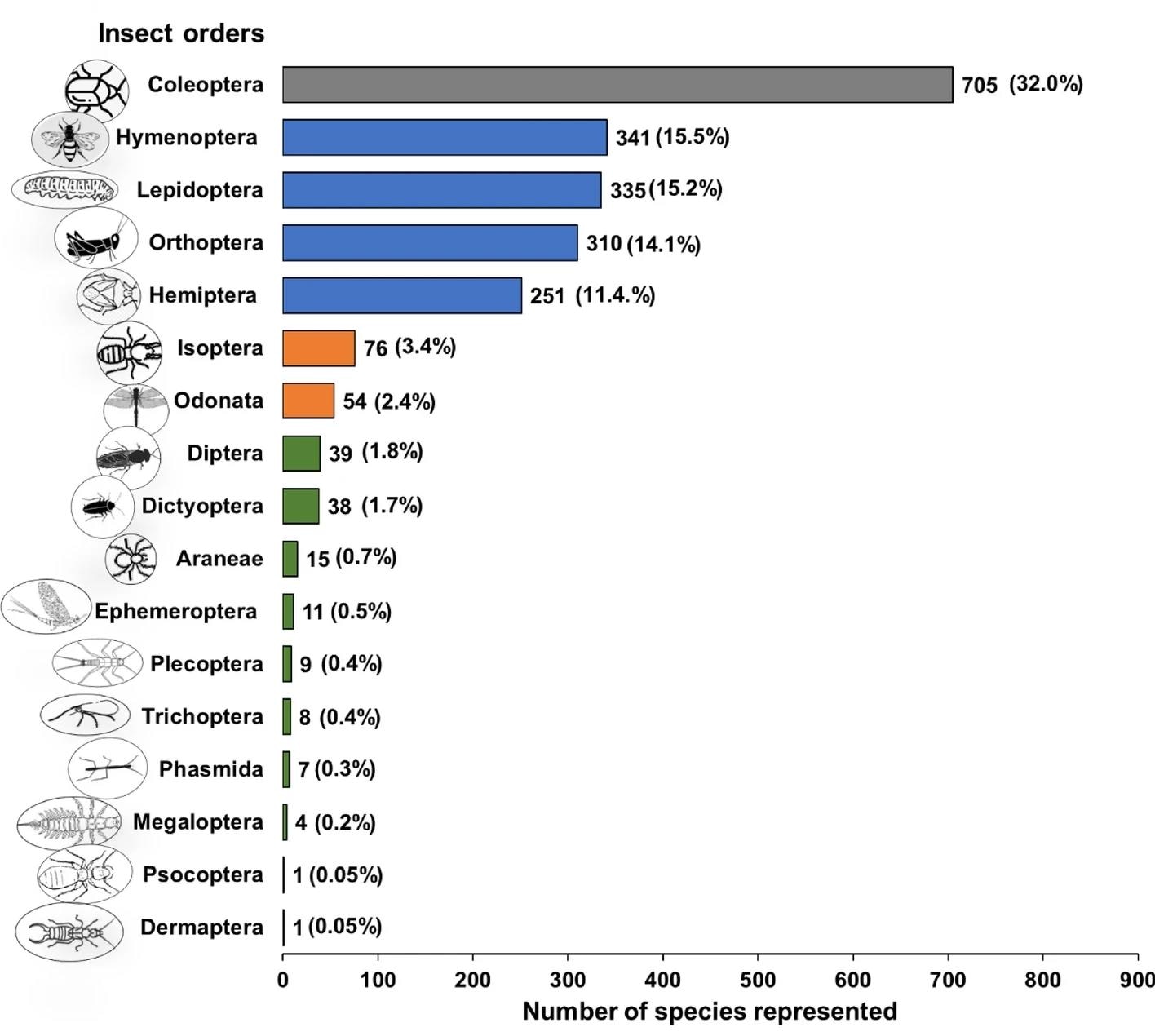

Global distribution of edible insect species by taxonomic order. Grey represents ≥ 500 species, Blue = 100–499 species, orange = 50–99 species, and green 1–49 species.1

Nutrient density and macronutrient profile

Edible insects typically provide approximately 35–75% crude protein on a dry-weight basis2,4, supplying all essential amino acids. Protein digestibility is generally comparable to milk, soy, and casein, although values vary by species, life stage, and processing method.2

Lipids comprise 10–50% of insects’ dry weight and are predominantly unsaturated, often accounting for 57–75% of total fat. Edible insects also contribute intrinsic dietary fiber primarily through chitin in the exoskeleton.4 Together, this macronutrient combination supports insects as compact, nutrient-dense alternatives to conventional animal foods.2

Vitamins and minerals

Edible insects provide multiple micronutrients, including iron, zinc, calcium, vitamin B12, riboflavin, and thiamine. Many species contain mineral concentrations comparable to or exceeding those found in beef, poultry, and some legumes.

Reported iron and zinc concentrations commonly range from approximately 5–60 mg/100 g and 8–27 mg/100 g dry matter, respectively, depending on species, developmental stage, and rearing substrate.2,4 These profiles position insects as flexible and micronutrient-rich ingredients in regions where deficiencies remain prevalent.

Protein quality and digestibility

Insect proteins provide high-quality, bioavailable amino acids that meet adult nutritional requirements. Digestibility values are similar to those of conventional animal proteins when antinutritional factors are minimized through appropriate processing.2

Protein extraction techniques, such as alkaline/isoelectric precipitation and ultrasound-assisted processing, increase protein yield while largely preserving amino acid composition, though structural modifications may occur that affect allergenicity and functional properties.2

Image Credit: BartTa / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: BartTa / Shutterstock.com

Fatty acids and lipids

Edible insects, particularly in larval and pupal stages, provide 10–50% lipids by dry weight, with a high proportion of unsaturated fatty acids including linoleic and α-linolenic acids.2,4 Many insect oils are liquid at room temperature, reflecting their favorable lipid profiles.

Fatty acid composition varies substantially by species and life stage, with linoleic acid often dominant in crickets and mealworms, and oleic acid more prevalent in several beetle larvae.2

Fiber, chitin, and digestive health

Chitin, the structural polysaccharide in insect exoskeletons, contributes to insoluble dietary fiber when insects are consumed whole or minimally processed. Chitin and its derivative, chitosan, have been associated with prebiotic effects and modulation of the gut microbiota.

Humans express acidic mammalian chitinase, indicating partial capacity to degrade chitin; however, digestibility and physiological effects depend strongly on processing methods, particle size, and degree of deacetylation.4

Should we all be eating insects? - BBC REEL

Sustainability and nutritional implications

Edible insects require significantly fewer resources than conventional livestock and can be reared on organic side streams, supporting circular food systems.

However, only a small proportion of edible insect species (approximately 6%) are currently domesticated or farmed at scale, with most species still harvested from the wild.1 Despite this limitation, insects provide nutritionally complete proteins, favorable lipid profiles, and bioavailable minerals, reinforcing their combined role in sustainability and human nutrition.3,4

Allergenicity and safety considerations

Edible insects are generally safe when properly produced and prepared; however, individuals with shellfish allergies may experience cross-reactivity due to shared allergens such as tropomyosin.

Food safety risks depend heavily on rearing substrate, environmental exposure, and processing conditions, as insects may accumulate heavy metals or microbial contaminants if these conditions are not properly managed.4 Thermal processing reduces microbial load but may not eliminate spores.

Long-term human dietary intervention data remain limited, and further research is required to assess chronic consumption effects, allergenicity, and species-specific nutritional variability.4

References

- Omuse, E. R., Tonnang, H. E. Z., Yusuf, A. A., et al. (2024). The global atlas of edible insects: analysis of diversity and commonality contributing to food systems and sustainability. Scientific Reports 14. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-024-55603-7. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-024-55603-7

- Li, M., Mao, C., Li, X., et al. (2023). Edible Insects: A New Sustainable Nutritional Resource Worth Promoting. Foods 12(22). DOI: 10.3390/foods12224073. https://www.mdpi.com/2304-8158/12/22/4073

- Aidoo, O.F., Osei-Owusu, J., Asante, K., et al. (2023). Insects as food and medicine: A sustainable solution for global health and environmental challenges. Frontiers in Nutrition 10. DOI: 10.3389/fnut.2023.1113219. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/nutrition/articles/10.3389/fnut.2023.1113219/full

- Gebreyes, B. G. & T. A. Teka. (2025). The Environmental and Ecological Benefits of Edible Insects: A Review. Food Science & Nutrition 13(6). DOI: 10.1002/fsn3.70459. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/fsn3.70459

Further Reading

Last Updated: Jan 28, 2026