Doctors tested fecal transplants from donor gut bacteria in frail hospital patients. Could this be the next tool to fight deadly drug-resistant infections?

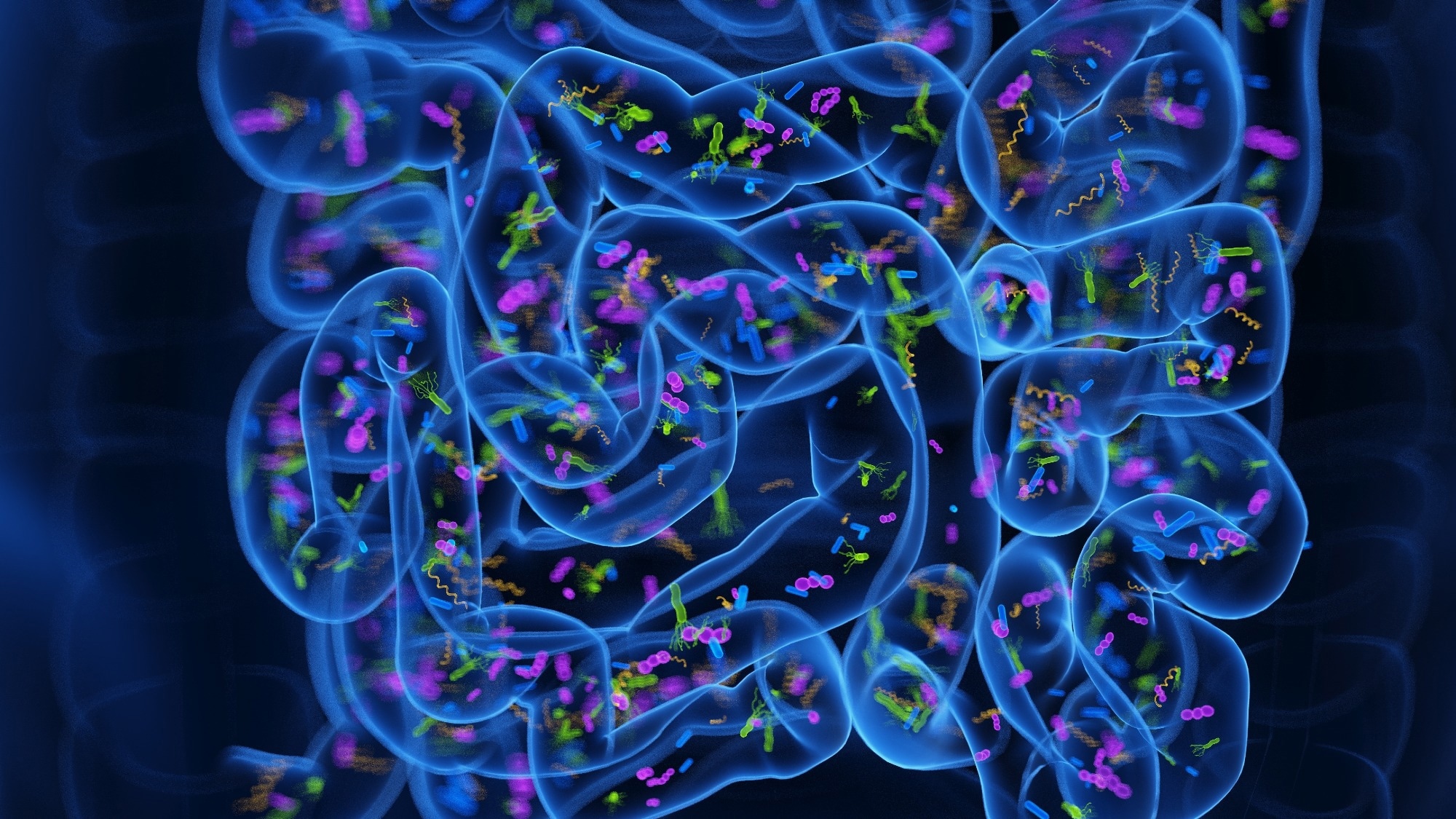

Study: Microbiota Transplantation Among Patients Receiving Long-Term Care. Image credit: 3dMediSphere/Shutterstock.com

Study: Microbiota Transplantation Among Patients Receiving Long-Term Care. Image credit: 3dMediSphere/Shutterstock.com

A non-randomized clinical trial examining the safety and acceptability of fecal microbiota transplantation in long-term acute care hospital patients revealed that the intervention is safe and well-tolerated. A detailed trial report is published in JAMA Network Open. This could potentially reduce some infection-related outcomes, although in this pilot study, all recipients remained colonized with at least one multidrug-resistant organism (MDRO) at follow-up.

Background

Multidrug-resistant microbial colonization in the intestine is associated with an increased risk of systemic infection and transmission, particularly in patients receiving long-term care in hospitals while recovering from critical illnesses. However, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not approved effective interventions to manage these conditions.

Emerging evidence indicates that microbiome interventions, such as fecal microbiota transplantation, are being investigated for their potential to reduce infection risk, antibiotic treatment duration, and hospital stay in patients with intestinal multidrug-resistant microbial colonization. However, results have been mixed across different settings and patient populations, and some prior evidence comes from indirect findings or from groups not exclusively colonized with MDROs.

In this single-center nonrandomized clinical trial, researchers investigated the safety and acceptability of fecal microbiota transplantation in long-term acute care hospital patients.

Trial design

The trial enrolled 42 patients with intestinal multidrug-resistant microbial colonization from a long-term acute care hospital in Atlanta, Georgia.

Of enrolled patients, 10 received fecal microbiota from healthy donors via gastrostomy tube or enema without antibiotic or bowel preparation conditioning. The remaining 32 patients were the control group and did not receive fecal microbiota transplantation.

The frequency and severity of adverse events related to fecal microbiota transplantation were assessed and compared with those of the control group. The proportion of patients with positive MDRO stool culture results after six months of transplantation was also evaluated.

Trial findings

The safety assessment at the six-month follow-up revealed that fecal microbiota transplantation is not associated with any severe adverse events. Adverse events reported after the transplantation were generally mild.

The most noticeable non-severe adversity in one patient was vomiting after administration of the fecal microbiota via gastrostomy tube. Two patients died after the transplantation; however, the deaths were not related to the transplantation, but instead were associated with the medical complexities of the patients.

The assessment of intestinal microbial colonization revealed that patients with fecal microbiota transplantation have fewer episodes of systemic bacterial infection, decreased pathogen intestinal dominance, and fewer days of antibiotic therapy than control patients. Still, these findings were exploratory, based on post hoc analyses, and not statistically significant.

Compared to 19% of control patients, none of the fecal microbiota transplantation recipients had positive blood cultures six months after the treatment, though this difference did not reach statistical significance.

Despite these trends, all fecal microbiota transplantation recipients remained positive for at least one MDRO in perirectal cultures at follow-up, and 60% acquired a new MDRO category during the study.

Significance

The trial findings indicate that healthy donor-derived fecal microbiota administered via gastrostomy or enema instillation is well tolerated and safe for long-term acute care hospital patients with intestinal multidrug-resistant microbial colonization.

The trial also suggests that fecal microbiota transplantation can potentially reduce systemic bacterial infection, intestinal pathogen domination, and antibiotic use in this high-risk population. However, the small sample size and study design limit definitive conclusions about efficacy.

MDRO intestinal colonization increases the risk of systemic and urinary tract infection. Existing evidence highlights the significance of fecal microbiota transplantation in reducing mortality, systemic infection, and health care utilization, even among patients with persistent multidrug-resistant microorganism-positive culture results. This study also observed increased gut microbial diversity among fecal microbiota transplantation recipients, suggesting a possible microbiome shift despite persistent colonization.

The current trial highlights the acceptability, safety, and potential efficacy of a single fecal microbiota transplantation. These pilot findings highlight the need for further large-scale clinical trials to explore whether increased doses, more frequent dosing, or conditioning regimens with antibiotics or laxatives can more effectively prevent microbial colonization in the intestine.

Given the current unavailability of FDA-approved therapies, optimizing microbiota conditioning and dosing strategies would be particularly beneficial for long-term acute care hospitals and other health care facilities that treat patients with a high prevalence of intestinal multidrug-resistant microbial colonization.

Patients were not randomly assigned to the intervention and control groups in this trial, and the treatment was not concealed. Future trials should consider these factors for a more conclusive interpretation.

The trial measured treatment-related outcomes using qualitative culture methods, with positive or negative results. Therefore, it could not provide information on potential quantitative reductions in pathogen density following fecal microbiota transplantation.

Long-term acute care hospital patients are at a higher risk of mortality from various medical complications and require frequent empirical antibiotic treatments. Moreover, the burden of colonized patients, particularly with multidrug-resistant bacteria, in a hospital unit further increases the risk of acquisition of new microbial colonization after fecal microbiota transplantation. These competing risks may bias clinical outcomes associated with the intervention.

The progression from colonization to infection is relatively rare in many populations, making this a challenging endpoint. Studying interventions in patients with a higher colonization prevalence and colonization to infection progression increases the efficiency of measuring these critical endpoints, but also potentially increases the frequency of competing risks with many safety and efficacy outcomes.

As the researchers stated, these limitations are offset by the demonstration of the feasibility of screening for microbiome interventions with facility-wide prevalence sampling followed by targeted treatment.

Download your PDF copy now!