Growing up poor may leave a lasting biological imprint, increasing the odds of frailty decades later—evidence from nearly 80,000 adults across 29 countries underscores the lifelong toll of early deprivation.

Study: Growing up in poverty, growing old in frailty: the life course shaping of health in the United States, England and Europe—a prospective and retrospective study. Image Credit: jrmiller482 / Shutterstock

Study: Growing up in poverty, growing old in frailty: the life course shaping of health in the United States, England and Europe—a prospective and retrospective study. Image Credit: jrmiller482 / Shutterstock

In a recent article published in the journal Scientific Reports, Gindo Tampubolon, a researcher at the University of Manchester, UK, investigated whether people who experienced poverty during their childhood are more likely to develop signs of frailty in their old age.

The analysis’s findings indicated that childhood poverty was significantly associated with an increased probability of frailty during later life, with women overall showing higher probabilities of frailty. Other contributing factors to frailty, including childhood illness, wealth, and education, highlighted the long-term effects of deprivation during early life on health.

Background

Childhood poverty is known to increase the risk of health problems in later life, such as disability, poor mental and cognitive function, and physical decline. Previous research has found that adults who grew up poor tend to have worse muscle strength, mood, and memory in old age across 29 high-income countries..

Researchers consider these findings to be evidence for the concept of the “long arm of childhood conditions,” which suggests that early life adversity can have lasting effects throughout life.

However, less is known about whether it also contributes to frailty, an age-related condition involving declines across multiple organ systems and leading to worse clinical outcomes and higher healthcare costs.

About the study

In this study, the author tested whether childhood poverty predicts frailty in older adults, even after considering factors from later life such as education, marital status, and adult health.

Using data from three large-scale aging studies representing nearly 80,000 older adults from the United States, England, and Europe, the study investigated whether poor material conditions in childhood still impact frailty in people aged 50 and above. The research also considers the role of social determinants of health across the life course and examines whether the effects differ by sex or country.

The study used the frailty phenotype approach developed by Fried and colleagues. This approach defines frailty as meeting at least three out of five indicators: exhaustion, unintended weight loss, weakness, low energy, and slowness. To ensure comparability, this binary outcome (frail vs. non-frail) was consistently applied across the three datasets though slowness was measured via walking speed tests in the U.S. and England but self-reported mobility issues in Europe.

Childhood poverty was assessed using retrospective self-reports from participants aged 50–95 (average age 66). Due to the possibility of recall errors, especially in older participants, the study employed a latent class approach to reduce recall bias and measurement error, constructing a more reliable measure of childhood poverty.

Data from the British and European surveys included indicators like the number of rooms, access to indoor plumbing, and heating. The American survey used more financially oriented indicators, such as moving due to financial hardship. Despite differences across regions, these variables were harmonized using established methods from earlier studies.

A fixed effects probit model including country fixed effects to account for differences in healthcare systems was used to estimate the association between childhood poverty and frailty, adjusting for confounding variables across the life course (e.g., parental occupation, youth illness, current age, sex, education, wealth, and marital status).

Findings

The study analyzed data from the United States, England, and 27 European countries, focusing on those who completed retrospective interviews. The analytic sample comprised 57% females, the mean age was 66.3 years, and 25.6% in Europe, 6% in the U.S., and 18.6% in England had experienced childhood poverty.

A fixed effects probit model revealed that childhood poverty significantly increased the likelihood of frailty in old age. Women were more likely to be frail overall, while higher education and wealth were protective factors. Illness in youth and having a father in a manual occupation were also associated with increased frailty.

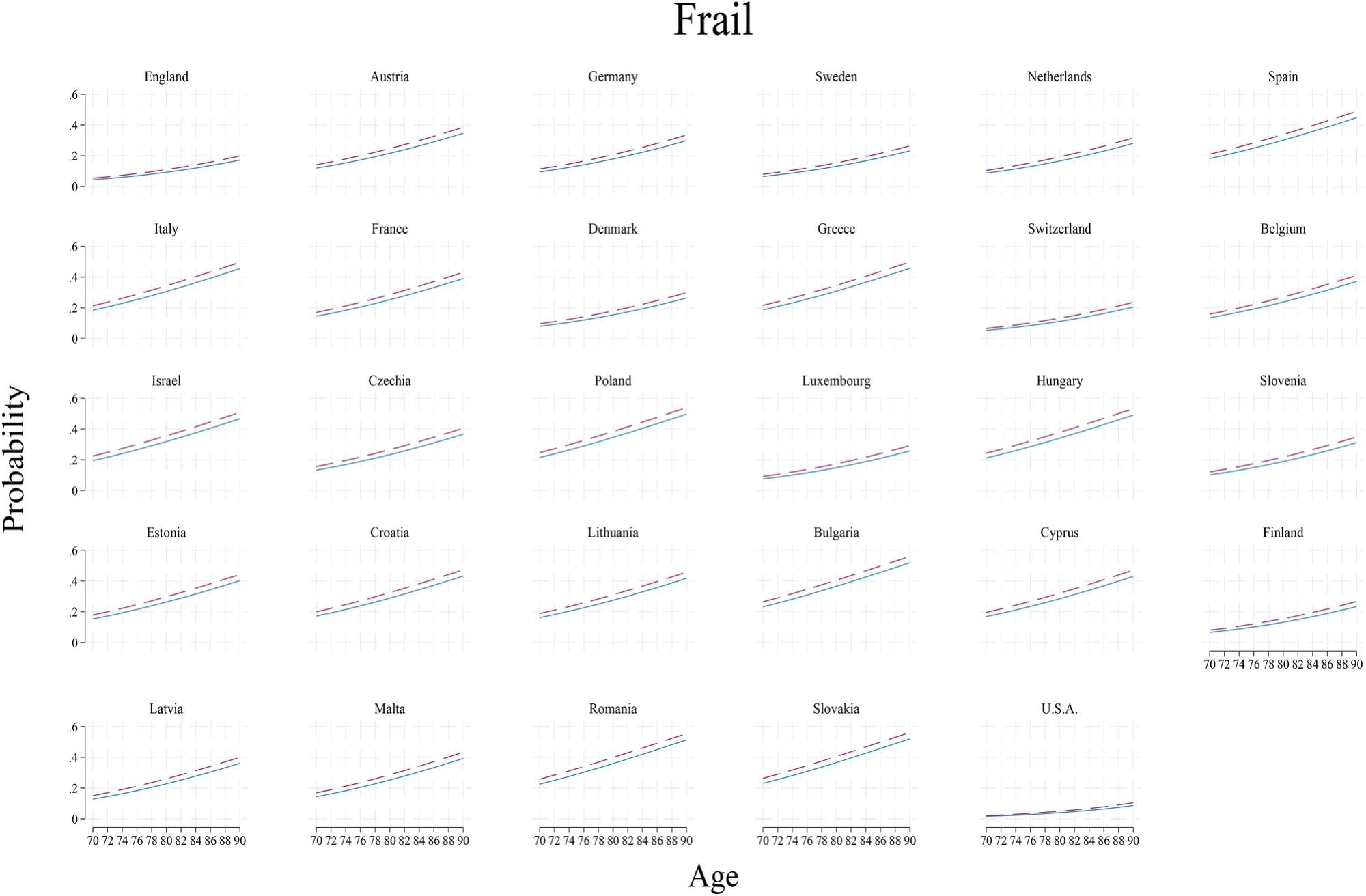

Country-specific plots (including the U.S. and England) showed that childhood poverty consistently elevated frailty risk between ages 70 and 90, with significant regional differences across Europe and an overall frailty prevalence of 1.7% in the U.S., 4.3% in England, and 13.4% in Europe. Sensitivity analyses using random effects and sex-stratified models confirmed the robustness of these findings.

Overall, childhood poverty emerged as a strong, persistent determinant of frailty in later life across diverse health systems in high-income countries.

Probabilities of Frail among the childhood poor (dash) and non-poor (solid) in older people aged 70–90 years in U.S., England and Europe based on models in Table 3 where all covariates are set at the sample averages. Analysis of HRS, ELSA and SHARE.

Probabilities of Frail among the childhood poor (dash) and non-poor (solid) in older people aged 70–90 years in U.S., England and Europe based on models in Table 3 where all covariates are set at the sample averages. Analysis of HRS, ELSA and SHARE.

Conclusions

This study offers the first comprehensive cross-national evidence from 29 high-income countries linking childhood poverty to frailty in old age. Despite differences in health systems and welfare support, the association holds across nations.

These findings suggest that childhood poverty may cause long-term biological effects, possibly through epigenetic changes (including accelerated epigenetic aging observed in prior U.S. research) as a hypothesized mechanism, predisposing individuals to frailty. While some earlier studies showed weaker associations, variations in methodology and social systems (e.g., Sweden’s welfare model) may explain differences.

The study’s strengths include its broad international scope and use of latent constructs to reduce error in retrospective data. However, its observational nature limits causal inference, and survivor and selection biases remain concerns.

Future research should explore low- and middle-income countries where childhood poverty is more prevalent, aligning with the goals of the UN Decade of Healthy Ageing. Addressing childhood poverty is essential to improving health outcomes across the life course.

Journal reference:

- Growing up in poverty, growing old in frailty: the life course shaping of health in the United States, England and Europe—a prospective and retrospective study. Tampubolon, G. Scientific Reports (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-025-99929-2, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-025-99929-2