The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the pathogen responsible for the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), is only one of many viruses that consist of a ribonucleic acid (RNA) genome.

Study: Low Density Lipoprotein Receptor-Related Protein 1 (LRP1) is a Host Factor for RNA Viruses Including SARS-CoV-2. Image Credit: Andrii Vodolazhskyi / Shutterstock.com

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Introduction

The majority of large or global outbreaks of disease are caused by enveloped RNA viruses. In the current study, the researchers aimed to identify host cell factors that promoted RNA virus replication.

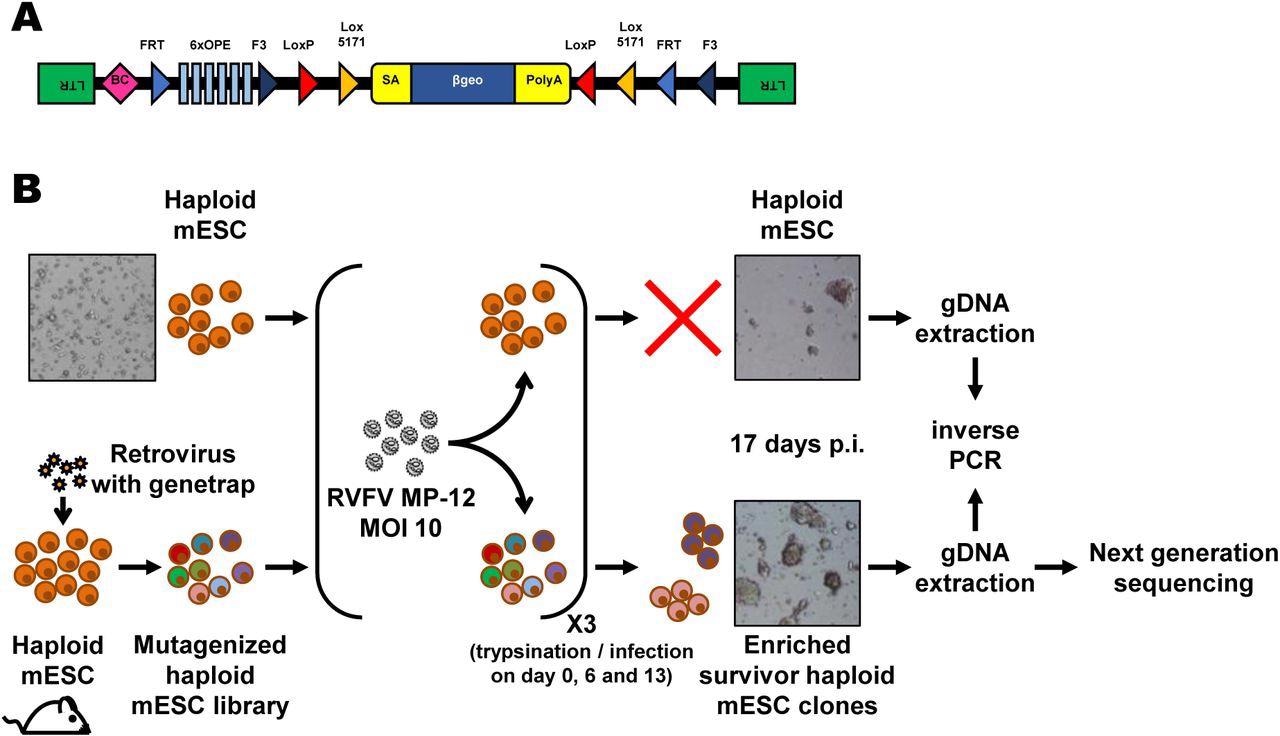

The researchers utilized the Rift Valley fever virus (RVFV) in the current study, as it is one type of virus that is considered one of the greatest public health risks. A haploid cell library with insertion mutations at different positions was used to identify clones that resisted infection with RVFV, as this would indicate the absence of a gene required for active or productive infection.

To this end, the LRP1 protein was a top hit. Moreover, LRP1 is a large receptor molecule on the cell membrane that binds over 40 ligands, thereby facilitating their entry into the cell. LRP1 also participates in several cellular activities including migration, proliferation, and differentiation, in addition to regulating multiple pathways including inflammation, JAK/STAT and ERK1/2 signaling pathways, and cholesterol homeostasis.

LRP1 deficiency led to reduced RVFV attachment to the cell and cell entry, leaving viral RNA production intact. Other experiments showed that this molecule also provides access to several other related and unrelated viruses, especially to SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2, that appear to be “among the most LRP-1-dependent viruses.”

However, LRP1 appears to affect different infection steps with different pathogens. This indicates that this protein may be a broadly acting host cell factor that promotes viral infection at various steps of the replication cycle.

Study findings

The LRP-1 mutation was found to confer a growth advantage on infected cells when exposed to the RVFV variant, which was greater when compared to the survival benefit associated with mutations in other published host factors. When LRP1 knockout in cell culture was conducted, RVFV gene expression was reduced both at five and 24 hours post-infection (hpi).

Forward genetics screen of the haploid mouse embryonic stem cell library for resistance to RVFV MP-12. (A) Schematic representation of the retroviral revertible genetrap used for mutagenesis. BC, barcode; OPE, Oct4 binding sites; SA, splicing acceptor site. (B) Experimental workflow for the RVFV MP-12 resistance screen using insertional mutagenesis. Bright-field microscopy images of the cells before infection and at the end of the screening process are shown as examples. mESC, mouse embryonic stem cells; p.i, post-infection; RVFV, Rift Valley fever virus.

This was followed by knocking out the gene in another host cell line with strong LRP1 expression. While viral nucleocapsid protein levels were unchanged from wild-type cells, viral gene expression was reduced by more than half as early as five hpi. This suggests that the LRP1 receptor maintains RVFV RNA levels constant within the host cells, but is not required for progeny virion production.

In fact, its early impact suggests that LRP1 is required for viral attachment. However, when a virulent strain was used, RNA synthesis recovered by 24 hpi, which did not occur in the previous in vitro experiment. Thus, LRP1 appears to act as a cofactor, rather than the primary receptor for RVFV infection.

LRP1 is also involved in viral attachment, as well as in the subsequent steps of infection for different viruses such as Sandfly fever Sicilian virus (SFSV), vesicular stomatitis (VSV), the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), SARS-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2. Notably, both SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 appear to depend on LRP1 at all stages of viral replication.

At 24 hpi, the scientists observed, “While for all other tested viruses the typical reduction in viral RNA was around 50%, and remained stable, for both SARS-coronaviruses, the RNA levels remained low over time, resulting in a 50 to over 95% reduction relative to the LRP1-expressing cells.”

For SARS-CoV-2, LRP1 knockdown in a human lung epithelial cell line, viral RNA synthesis was reduced at 5 hpi and 24 hpi. However, since this cell line expresses low LRP1 levels as compared to its natural state, another cell line with higher LRP1 expression was used to repeat this experiment. This second experiment showed dramatic reductions in viral nucleocapsid protein and virion yields in the cell supernatant that persisted until the end of the replication cycle.

A cell-dependent effect was thus observed, wherein viral infection was promoted, even at the attachment phase and, in some cases, even later phases. LRP1 may therefore have a supporting role in RNA synthesis, as well as in early infection.

Implications

The study findings demonstrate results show that LRP1 is involved in viral envelope binding and internalization, as well as later stages of infection. Moreover, this protein may carry factors required for SARS-like coronavirus RNA replication during its cycling between cell membrane and endosomes.

Interestingly, MERS-CoV did not appear to need for LRP1 in the late stage of infection, which was unlike the findings for both SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2. This difference could only impact viral attachment or have only a non-obligate requirement in the later stages of infection with MERS-CoV.

It is possible that LRP1 contributes to the specificity of cell infection by SARS-CoV-2 since it is found on hepatic cells, the brain, the respiratory system, kidneys, and other tissues. Notably, the brain microglia and astrocytes, liver cells, skeletal muscle cells, blood monocytes, and macrophages are all known to have the highest LRP1 expression in the body.

We have identified LRP1 as a broadly active pro-viral factor that enables entry of RNA viruses. In some cases, LRP1 is also facilitating the late stage of infection.”

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Journal references:

- Preliminary scientific report.

Devignot, S., Sha, T. W., Burkard, T., et al. (2022). Low Density Lipoprotein Receptor-Related Protein 1 (LRP1) is a Host Factor for RNA Viruses Including SARS-CoV-2. bioRxiv. doi:10.1101/2022.02.17.480904. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.02.17.480904v1

- Peer reviewed and published scientific report.

Devignot, Stephanie, Tim Wai Sha, Thomas R. Burkard, Patrick Schmerer, Astrid Hagelkruys, Ali Mirazimi, Ulrich Elling, Josef M. Penninger, and Friedemann Weber. 2023. “Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor–Related Protein 1 (LRP1) as an Auxiliary Host Factor for RNA Viruses.” Life Science Alliance 6 (7). https://doi.org/10.26508/lsa.202302005. https://www.life-science-alliance.org/content/6/7/e202302005.