Transcription Factors (TFs) are pivotal regulators of gene expression and have been implicated in a variety of diseases, including cancer, neurological disorders, autoimmune conditions, and metabolic diseases. Once deemed "undruggable," TFs are now being therapeutically targeted through selective modulators, degraders, and innovative strategies such as PROTACs.

Recent approvals by the FDA, including belzutifan for VHL-associated renal cell carcinoma and elacestrant for breast cancer, underscore significant clinical advancements.

The development of PROTACs and direct small-molecule inhibitors, such as those targeting FOXA1, is broadening therapeutic options. Technologies like artificial intelligence, RNA interference, CRISPR, and engineered modulators are also expected to enhance precision in treatment.

These innovations are reshaping treatment paradigms, offering renewed hope for patients with previously untreatable or challenging diseases.

The master regulators

The human genome encodes approximately 1,600 TFs, representing one of the largest protein families within an intricate regulatory network that dictates the timing, location, and manner of gene expression.1

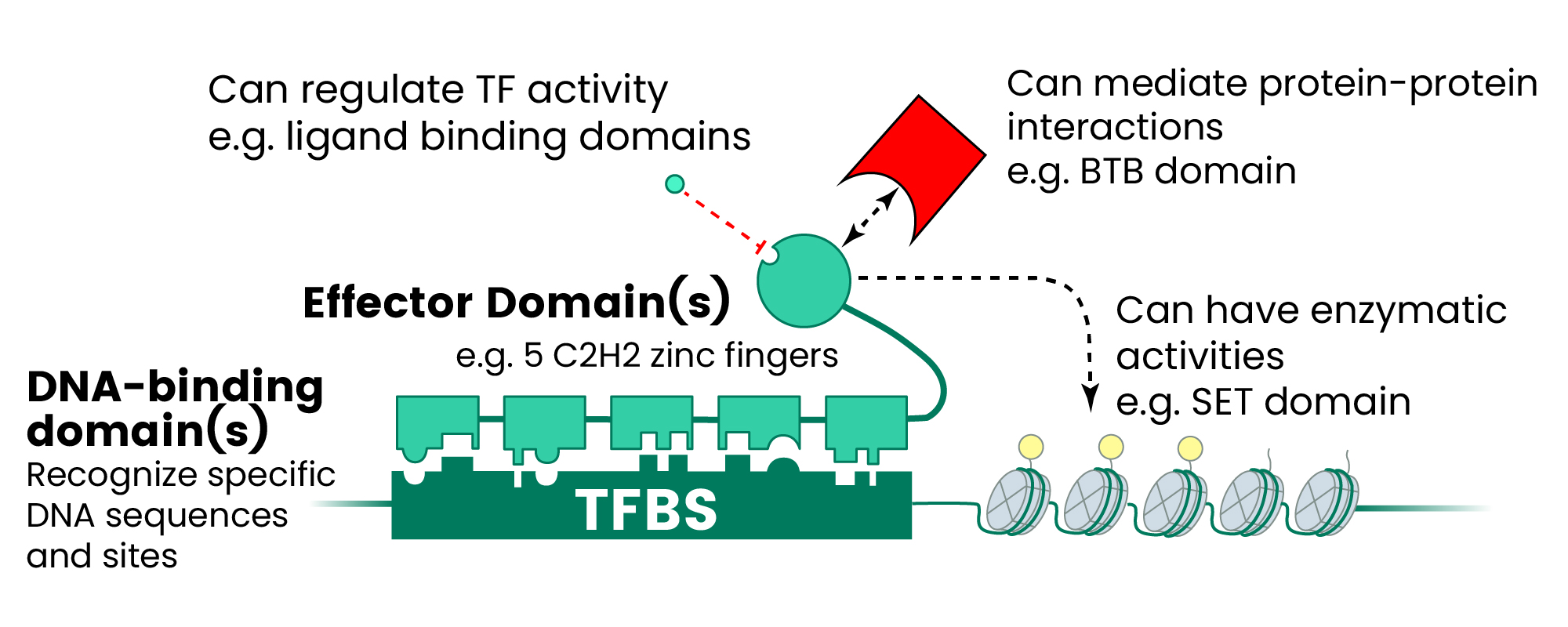

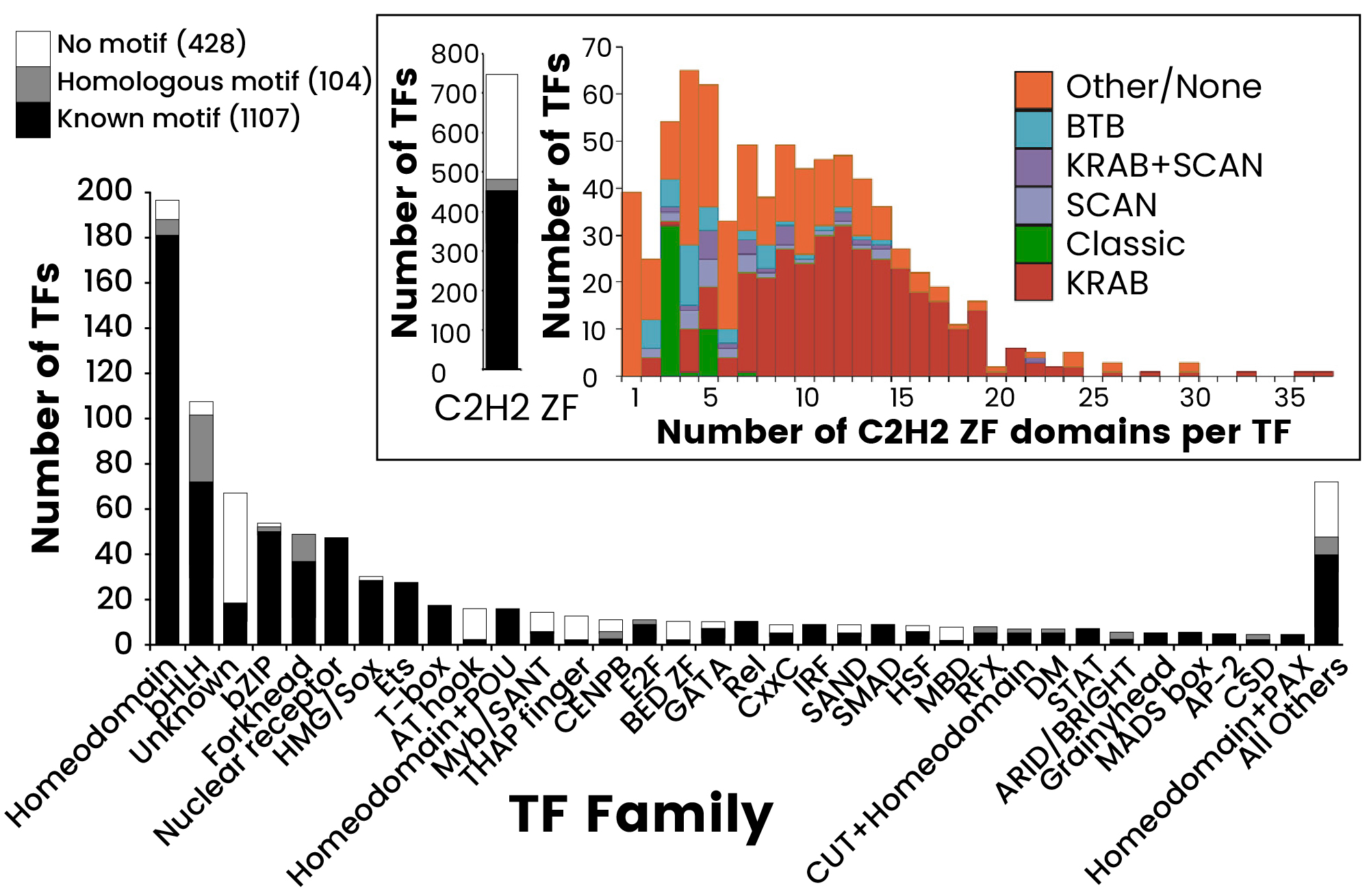

These molecular regulators achieve specificity through diverse DNA-binding domains that recognize particular nucleotide sequences, influencing cellular fate and responses to pathological conditions (see Figure 1).1-3

Figure 1. The Human TF Repertoire1. (A) Schematic of a prototypical TF. (B) Number of TFs and motif status for each NA-binding domain (DBD) family. Inset displays the distribution of the number of C2H2-ZF domains for classes of effector domains (KRAB, SCAN, or BTB domains); “Classic” indicates the related and highly conserved SP, KLF, EGR, GLI GLIS, ZIC, and WT proteins. Image Credit: Sino Biological Inc.

Disease mechanisms associated with TFs

Over 19% of TFs have been linked to at least one disease phenotype.1 Cancer is the most extensively investigated category concerning transcription factor dysregulation, with multiple TFs driving distinct oncogenic mechanisms.2,4,5,6

Hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs), ETS-1, MYC, and β-catenin act as master regulators that constitutively activate oncogenic pathways, fostering tumor cell proliferation, survival, metastatic spread, and altered metabolism.

Conversely, mutations in p53 disrupt essential tumor suppression mechanisms, allowing uncontrolled cellular growth across breast, prostate, and hematologic malignancies.2

Hormone-dependent cancers significantly depend on FOXA1 and ESR1 for tumorigenesis in breast and prostate tissues, while STAT3 promotes cancer cell survival and facilitates immune evasion across various cancer types.5 Furthermore, KLF5 and BRD4 regulate oncogenic transcription programs specifically in basal-like breast cancer.5

In autoimmune diseases, TFs disrupt immune homeostasis through various mechanisms. Tcf1 and Lef1 are crucial for maintaining CD8+ T-cell identity, and their disruption skews CD4+/CD8+ ratios, compromising immune function.7

STAT3 and STAT6 mediate inflammatory pathways in atopic dermatitis and hidradenitis suppurativa, while IRAK4 drives inflammation in hidradenitis suppurativa, presenting an attractive target for degrader therapies.8 The NF-κB/STAT/AP-1 axis synergistically activates pro-inflammatory genes in synovial cells, perpetuating joint destruction in rheumatoid arthritis.9-11

Neurological disorders feature TFs that regulate neural development and survival pathways. POU3F2 governs genes involved in neocortical development, with dysregulation associated with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.12

FOXO family members influence neuronal survival and autophagy, contributing to neurodegeneration when dysfunctional.13 TFEB regulates lysosome biogenesis, and its impaired function exacerbates Alzheimer's pathology.14,15

Metabolic diseases predominantly involve TFs that regulate glucose homeostasis and adipose tissue function. HNF1α and HNF4α are key regulators of insulin production and glucose metabolism, with mutations leading to maturity-onset diabetes (MODY).15

HOXA5 regulates adipocyte differentiation and distribution; deficiencies in HOXA5 drive obesity-related inflammation and insulin resistance.16 FOXM1 plays a role in diabetic complications through endothelial dysfunction.17

Cardiovascular diseases involve BRD4, MED1, and EP300, which stabilize DNA loops that regulate cardiac gene expression.18 Their dysregulation contributes to congenital heart disease and atherosclerosis by disrupting cardiac transcriptional programs.18

TFs as therapeutic targets

Unlike enzymes with clearly defined active sites, TFs operate through relatively featureless protein-protein and protein-DNA interaction surfaces. Historically, TFs have been deemed "undruggable" due to the absence of traditional binding pockets amenable to small-molecule drugs.19 However, advancements in research have begun to address these challenges.

In the 1970s, the development of tamoxifen—a selective estrogen receptor modulator—revolutionized breast cancer treatment by demonstrating that TFs could be targeted with competitive antagonists.20,21

This innovation marked one of the first rational drug design strategies aimed at directly inhibiting TFs. Similarly, extensive research has focused on the creation of compounds that inhibit the activation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) for cancer therapy.22

Nuclear hormone receptor modulators and indirect targeting strategies continue to be the gold standard for TF therapeutics.23 Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) and degraders (SERDs), including fulvestrant, tamoxifen, and the recently approved elacestrant, are the most effective agents for hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. SERMs act as competitive antagonists to inhibit receptor activity, while SERDs promote receptor degradation through ubiquitin-proteasome pathways.21

Recently, belzutifan—the first direct small molecule inhibitor of HIF-2α—was approved in 2021 for von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease.24 This advancement illustrates the potential for directly targeting TF protein-protein interaction domains.25

The FDA has approved seven drugs targeting TF for the treatment of cancers, cardiovascular diseases, and autoimmune diseases (shown in Table 1).

Table 1. Featured FDA-Approved TF Inhibitors. Source: Sino Biological Inc.

| Drug Name |

TF Target |

Primary Indication(s) |

FDA Approval Date |

| Dexamethasone |

NR3C1

(Glucocorticoid R) |

Cancer, asthma,

immune disorders |

October 30, 195826 |

| Carvedilol |

HIF1A |

Heart failure,

hypertension |

March 27, 200327 |

Dimethyl

fumarate |

RELA

(NF-κB subunit) |

Multiple sclerosis,

psoriasis |

March 27, 201328 |

| Sulfasalazine |

NF-κB |

RA, IBD |

April 13, 2005 (for juvenile

rheumatoid arthritis)29 |

| Eltrombopag |

TFEB |

Immune

thrombocytopenia |

June 11, 2015 (for pediatric

ITP, ages ≥6)30 |

| Belzutifan |

Hypoxia-Inducible

Factor 2α (HIF-2α) |

Von Hippel-Lindau Disease,

Renal Cell Carcinoma |

August 13, 202125 |

| Elacestrant |

Estrogen Receptor

α (ERα) |

ER+ Breast Cancer

with ESR1 mutations |

January 27, 202331 |

Breakthroughs in TF therapeutics

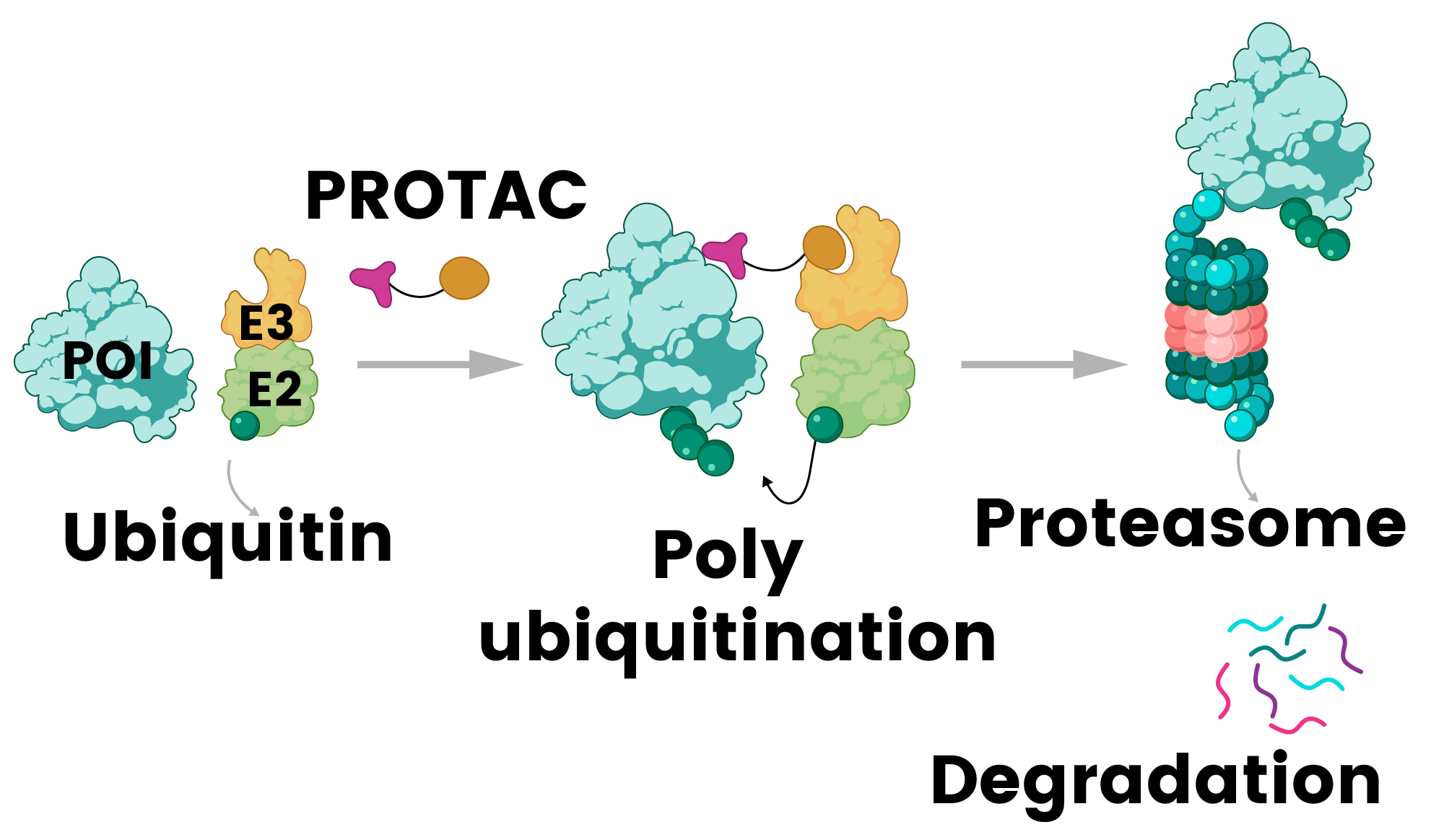

Significant advancements in TF therapeutics have occurred over the past decade, propelled by innovative approaches such as proteolysis targeting chimeras (PROTACs), combination strategies, and direct TF inhibitors.

Breakthroughs in PROTACs

PROTACs are the most clinically advanced strategy for targeting TFs since their initial design by Sakamoto and Crews in 2001.8,32,33,34 These bifunctional molecules concurrently bind target proteins and E3 ubiquitin ligases, facilitating selective protein degradation through the ubiquitin-proteasome system.33 TF-PROTACs have demonstrated efficacy against NF-κB and E2F, paving the way for novel therapeutic options for various diseases.34

Figure 2. PROTAC (proteolysis-targeting chimera) mechanism: a bifunctional molecule recruits E3 ligase to the protein of interest (POI), triggering its ubiquitination and subsequent degradation by the proteasome 32. Image Credit: Sino Biological Inc.

Table 2 outlines PROTAC compounds targeting TFs currently undergoing clinical trials.35 Notably, ARV-471 (vepdegestrant), which degrades the estrogen receptor, and BMS-986365 (CC-94676), targeting the androgen receptor, have exhibited strong clinical efficacy, achieving protein degradation rates exceeding 90% in cancer patients.36

In February 2024, the FDA granted vepdegestrant Fast Track designation for the treatment of ER+/HER2- advanced or metastatic breast cancer in adults previously treated with endocrine therapy.37

Table 2. PROTACs Targeting TFs in Clinical Trials. Source: https://synapse.zhihuiya.com/

| Drug |

Company |

Target |

Indications |

Status |

Vepdegestran

(ARV-471) |

Arvinas/Pfizer |

ER |

ER + /HER2- breast cancer |

Phase III |

CC-94676

(BMS-986365) |

BMS |

AR |

mCRPC |

Phase III |

| ARV-110 |

Arvinas |

AR |

mCRPC |

Phase II |

| ARV-766 |

Arvinas/Novartis |

AR |

mCRPC |

Phase II |

| GT-20029 |

Kintor Pharma |

AR |

Skin and Musculoskeletal

Diseases |

Phase II |

| RT3789 |

Prelude

Therapeutics |

SMARCA2 |

Metastatic Solid

Tumor, NSCLC |

Phase II |

| HRS-5041 |

Jiangsu HengRui |

ER |

mCRPC |

Phase I/II |

| HRS-1358 |

Jiangsu HengRui |

AR |

Breast cancer |

Phase I/II |

| AC-176 |

AccutarBio |

AR |

mCRPC |

Phase I |

| AC-699 |

AccutarBio |

ERα |

ER-positive/HER2-negative Br |

Phase I |

| ARV-393 |

Arvinas |

BCL6 |

Lymphoma |

Phase I |

| HSK-38008 |

Haisco |

AR-v7 |

mCRPC |

Phase I |

| HP518 |

Hinova |

AR |

mCRPC |

Phase I |

| KT-621 |

Kymera |

STAT6 |

atopic dermatitis |

Phase I |

| NX-2127 |

Nurix |

IKZF1/3 |

R/R B-cell malignancies |

Phase I |

mCRPC = Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer; NSCLC = Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

Breakthroughs in small molecules

Recent years have witnessed significant advancements in targeting challenging TFs through various mechanisms. Small molecule inhibitors targeting STAT3 have shown considerable promise in clinical trials.38,39

Although no STAT3 inhibitors have received FDA approval to date, the development of STAT3 PROTACs represents a promising approach to overcoming the difficulties associated with directly targeting this TF.40

NF-κB pathway inhibitors have also progressed through clinical development, with several small molecules targeting various components of this critical inflammatory TF pathway.41

These agents hold significant potential for treating inflammatory diseases, certain cancers, and autoimmune diseases driven by NF-κB. Notably, WX-02-23 represents a breakthrough as the first small molecule to directly bind the TF FOXA1, covalently targeting a cryptic cysteine residue (C258) when FOXA1 is bound to DNA, altering its binding specificity and demonstrating that TFs can be modulated through allosteric modulation.19

Future directions

Future therapeutics targeting TFs will focus on precision medicine and combination therapies. Artificial intelligence is accelerating drug discovery by utilizing machine learning to optimize drug design, predict binding sites, and identify patient-specific targets.42,43,44

Emerging technologies, such as CRISPR-based approaches, RNA interference, and engineered TF modulators, promise to transform the field.45,46,47 Such platforms allow for highly precise targeting of specific TF functions while minimizing off-target effects.

Featured products of transcription protein

Source: Sino Biological Inc.

| Cat# |

Product Name |

Species |

Molecule |

Expression System |

Tag |

| S54-54BH |

STAT3 Protein |

Human |

STAT3 |

Baculovirus-Insect Cells |

N-His |

| S54-54G |

STAT3 Protein |

Human |

STAT3 |

Baculovirus-Insect Cells |

N-GST |

| S55-54H |

STAT4 Protein |

Human |

STAT4 |

Baculovirus-Insect Cells |

N-His |

| A09-54G |

ATF1 Protein |

Human |

ATF1 |

Baculovirus-Insect Cells |

N-GST |

| S57-30H |

STAT6 Protein |

Human |

STAT6 |

Baculovirus-Insect Cells |

N-His |

| C06-30G |

Catenin beta Protein |

Human |

CTNNB1 |

Baculovirus-Insect Cells |

N-GST |

| S52-50G |

STAT1 alpha Protein |

Human |

STAT1 |

Baculovirus-Insect Cells |

N-GST |

| E64-30G |

ELK1 Protein |

Human |

ELK1 |

Baculovirus-Insect Cells |

N-GST |

| S57-30G |

STAT6 Protein |

Human |

STAT6 |

Baculovirus-Insect Cells |

N-GST |

| T74-34G |

TDP43 Protein |

Human |

TARDBP |

Baculovirus-Insect Cells |

N-GST |

| S11-30G |

SMAD2 Protein |

Human |

Smad2 |

E. coli |

N-GST |

| S52-54G |

STAT1 beta Protein |

Human |

STAT1 |

Baculovirus-Insect Cells |

N-GST |

| P07-31G |

P300 Protein |

Human |

EP300 |

Baculovirus-Insect Cells |

N-GST |

| S12-30G |

SMAD3 Protein |

Human |

Smad3 |

E. coli |

N-GST |

| S56-54BG |

STAT5B Protein |

Human |

STAT5b |

Baculovirus-Insect Cells |

N-GST |

| S10-30G |

SMAD1 Protein |

Human |

Smad1 |

E. coli |

N-GST |

| N30-34G |

NFE2L2 (NRF2) Protein |

Human |

NFE2L2 |

Baculovirus-Insect Cells |

N-GST |

| N13-31G |

NFKB2 Protein |

Human |

NFKB2 |

Baculovirus-Insect Cells |

N-GST |

| N12-30G |

NFATC1 Protein |

Human |

NFATC1 |

Baculovirus-Insect Cells |

N-GST |

| S53-54G |

STAT2 Protein |

Human |

STAT2 |

Baculovirus-Insect Cells |

N-GST |

| S14-30G |

SMAD5 Protein |

Human |

Smad5 |

E. coli |

N-GST |

| C06-30H |

Catenin beta Protein |

Human |

CTNNB1 |

Baculovirus-Insect Cells |

N-His |

| N12-35G |

NFKB1 (p50) Protein |

Human |

NFkB1 |

Baculovirus-Insect Cells |

N-GST |

| M86-30G |

MYC Protein |

Human |

MYC |

Baculovirus-Insect Cells |

N-GST |

| S52-54H |

STAT1 beta Protein |

Human |

STAT1 |

Baculovirus-Insect Cells |

N-His |

| S56-54H |

STAT5 Protein |

Human |

STAT5a |

Baculovirus-Insect Cells |

N-His |

| S12-31G |

SMAD3 (del SXS) Protein |

Human |

Smad3 |

E. coli |

N-GST |

| I20-30G |

IkBA Protein |

Human |

NFKBIA |

E. coli |

N-GST |

| H25-30G |

HSF1 Protein |

Human |

HSF1 |

E. coli |

N-GST |

| F66-30G |

FOS Protein |

Human |

FOS |

Baculovirus-Insect Cells |

N-GST |

Conclusions

TF therapeutics have progressed from concept to clinical reality, with multiple compounds entering late-stage trials and receiving regulatory approval.32 Advances in precision delivery, drug discovery, and personalized medicine now facilitate highly specific targeting of disease-driving mechanisms.48

As these therapies demonstrate safety and efficacy in autoimmune, oncology, and genetic diseases, they are set to redefine treatment paradigms and offer new hope to patients facing previously untreatable conditions.

References and further reading

- Lambert, S.A., et al. (2018). The Human Transcription Factors. Cell, (online) 172(4), pp.650–665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2018.01.029.

- Huilgol, D., et al. (2019). Transcription Factors That Govern Development and Disease: An Achilles Heel in Cancer. Genes, (online) 10(10). https://doi.org/10.3390/genes10100794.

- Lee, T. and Young, Richard A. (2013). Transcriptional Regulation and Its Misregulation in Disease. Cell, 152(6), pp.1237–1251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.014.

- Shiah, J.V., Johnson, D.E. and Grandis, J.R. (2023). Transcription Factors and Cancer. The Cancer Journal, (online) 29(1), pp.38–46. https://doi.org/10.1097/ppo.0000000000000639.

- Vishnoi, K., et al. (2020). Transcription Factors in Cancer Development and Therapy. Cancers, (online) 12(8). https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12082296.

- Hasan, A., et al. (2024). Deregulated transcription factors in the emerging cancer hallmarks. Seminars in Cancer Biology, (online) 98, pp.31–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcancer.2023.12.001.

- Shan, Q., et al. (2021). Tcf1 and Lef1 provide constant supervision to mature CD8+ T cell identity and function by organizing genomic architecture. Nature Communications, (online) 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-26159-1.

- Békés, M., Langley, D.R. and Crews, C.M. (2022). PROTAC targeted protein degraders: the past is prologue. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, (online) 21(3), pp.1–20. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41573-021-00371-6.

- Park, M. and Hong, J. (2016). Roles of NF-κB in Cancer and Inflammatory Diseases and Their Therapeutic Approaches. Cells, 5(2), p.15. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells5020015.

- Sun, S.-C., Chang, J.-H. and Jin, J. (2013). Regulation of nuclear factor-κB in autoimmunity. Trends in Immunology, (online) 34(6), pp.282–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2013.01.004.

- Aud, D. and Peng, S.L. (2006). Mechanisms of Disease: transcription factors in inflammatory arthritis. Nature Clinical Practice Rheumatology, 2(8), pp.434–442. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncprheum0222.

- Pearl, J.R., et al. (2019). Genome-Scale Transcriptional Regulatory Network Models of Psychiatric and Neurodegenerative Disorders. 8(2), pp.122-135.e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cels.2019.01.002.

- Santos, B.F., et al. (2023). FOXO family isoforms. Cell Death & Disease, (online) 14(10), pp.1–16. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-023-06177-1.

- Rai, S.N., et al. (2021). Therapeutic Potential of Vital Transcription Factors in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Disease With Particular Emphasis on Transcription Factor EB Mediated Autophagy. Frontiers in Neuroscience, (online) 15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2021.777347.

- Boj, S.F., et al. (2001). A transcription factor regulatory circuit in differentiated pancreatic cells. 98(25), pp.14481–14486. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.241349398.

- Parrillo, L., et al. (2023). The Transcription Factor HOXA5: Novel Insights into Metabolic Diseases and Adipose Tissue Dysfunction. Cells, (online) 12(16), p.2090. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells12162090.

- Zhao, B., et al. (2023). Role of transcription factor FOXM1 in diabetes and its complications (Review). International Journal of Molecular Medicine, (online) 52(5), p.101. https://doi.org/10.3892/ijmm.2023.5304.

- Mao, S., et al. (2024). Role of transcriptional cofactors in cardiovascular diseases. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, pp.149757–149757. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2024.149757.

- Lee, Y., et al. (2025). Advances in transcription factor delivery: Target selection, engineering strategies, and delivery platforms. Journal of Controlled Release, (online) 384, p.113885. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2025.113885.

- Moyer, C.L. and Brown, P.H. (2023). Targeting nuclear hormone receptors for the prevention of breast cancer. Frontiers in Medicine, (online) 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2023.1200947.

- Shah, M., et al. (2024). US Food and Drug Administration Approval Summary: Elacestrant for Estrogen Receptor–Positive, Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2–Negative, ESR1-Mutated Advanced or Metastatic Breast Cancer. Journal of clinical oncology. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.23.02112.

- Shirai, Y., et al. (2021). An Overview of the Recent Development of Anticancer Agents Targeting the HIF-1 Transcription Factor. Cancers, 13(11), p.2813. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13112813.

- Stephen, Cidlowski, J.A., et al. (2023). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2023/24: Nuclear hormone receptors. British Journal of Pharmacology, 180(S2). https://doi.org/10.1111/bph.16179.

- Toledo, R.A., et al. (2022). Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 2 Alpha (HIF2α) Inhibitors: Targeting Genetically Driven Tumor Hypoxia. 44(2), pp.312–322. https://doi.org/10.1210/endrev/bnac025.

- Wu, X., et al. (2025). Belzutifan for the treatment of renal cell carcinoma. Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology, (online) 17. https://doi.org/10.1177/17588359251317846.

- Raynor, J.W., Minor, W. and Chruszcz, M. (2007). Dexamethasone at 119 K. Acta Crystallographica Section E Structure Reports Online, 63(6), pp.o2791–o2793. https://doi.org/10.1107/s1600536807020806.

- FDA. (2025). Drug Approval Package: Coreg (Carvedilol) NDA #20-297/S9. (online) Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2003/20-297s009_Coreg.cfm.

- FDA. (2024). Drug Approval Package: Brand Name (Generic Name) NDA #. (online) Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2013/204063Orig1s000TOC.cfm.

- FDA. (2025). Drug Approval Package: Azulfidine (Sulfasalazine) NDA #21-243. (online) Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2000/21243_Azulfidine.cfm (Accessed 20 Aug. 2025).

- Ehrlich, L.A., et al. (2017). U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval summary: Eltrombopag for the treatment of pediatric patients with chronic immune (idiopathic) thrombocytopenia. Pediatric Blood & Cancer, 64(12). https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.26657.

- Research, C. for D.E. and (2023). FDA approves elacestrant for ER-positive, HER2-negative, ESR1-mutated advanced or metastatic breast cancer. FDA. (online) Available at: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-elacestrant-er-positive-her2-negative-esr1-mutated-advanced-or-metastatic-breast-cancer.

- Jung, H. and Lee, Y. (2025). Targeting the Undruggable: Recent Progress in PROTAC-Induced Transcription Factor Degradation. Cancers, 17(11), p.1871. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17111871.

- Sakamoto, K.M., et al. (2001). Protacs: Chimeric molecules that target proteins to the Skp1-Cullin-F box complex for ubiquitination and degradation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 98(15), pp.8554–8559. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.141230798.

- Liu, J., et al. (2021). TF-PROTACs Enable Targeted Degradation of Transcription Factors. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 143(23), pp.8902–8910. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.1c03852.

- PROTAC Clinical Progress Search Results - Global Drug Intelligence Database. Available from: Global landscape of PROTAC: Perspectives from patents, drug pipelines, clinical trials, and licensing transactions - ScienceDirect

- Wang, X., et al. (2024). Annual review of PROTAC degraders as anticancer agents in 2022. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, (online) 267, p.116166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmech.2024.116166.

- Pfizer (2024). Arvinas and Pfizer’s Vepdegestrant (ARV-471) Receives FDA Fast Track Designation for the Treatment of Patients with ER+/HER2- Metastatic Breast Cancer | Pfizer. (online) Pfizer. Available at: https://www.pfizer.com/news/announcements/arvinas-and-pfizers-vepdegestrant-arv-471-receives-fda-fast-track-designation.

- Lapidot, M., et al. (2020). Inhibitors of the Transcription Factor STAT3 Decrease Growth and Induce Immune Response Genes in Models of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma (MPM). Cancers, (online) 13(1), p.7. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13010007.

- Tsimberidou, A.M., et al. (2025). Phase I Trial of TTI-101, a First-in-Class Oral Inhibitor of STAT3, in Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors. Clinical Cancer Research, (online) 31(6), pp.965–974. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-24-2920.

- Vontz, G., et al. (2023). Abstract 1659: Development of HJC0152, its analogs and protein degraders to modulate STAT3 for triple-negative breast cancer therapy. Cancer Research, (online) 83(7_Supplement), pp.1659–1659. https://doi.org/10.1158/1538-7445.am2023-1659.

- Ramadass, V., Vaiyapuri, T. and Tergaonkar, V. (2020). Small Molecule NF-κB Pathway Inhibitors in Clinic. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, (online) 21(14). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21145164.

- Yu, Z. and Zhang, Y. (2024). Foundation model for modeling and understanding transcription regulation from genome. National Science Review, (online) 11(11). https://doi.org/10.1093/nsr/nwae355.

- Abid, D. and Brent, M.R. (2023). NetProphet 3: a machine learning framework for transcription factor network mapping and multi-omics integration. Bioinformatics, 39(2). https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btad038.

- Frömel, R., et al. (2025). Design principles of cell-state-specific enhancers in hematopoiesis. Cell. (online) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2025.04.017.

- Li, T., et al. (2023). CRISPR/Cas9 therapeutics: Progress and Prospects. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, (online) 8(1), pp.1–23. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-023-01309-7.

- Hao, L., et al. (2024). Targeting and monitoring ovarian cancer invasion with an RNAi and peptide delivery system. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 121(11). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2307802121.

- Sang, Y., Xu, L. and Bao, Z. (2024). Artificial transcription factors: technology development and applications in cell reprogramming, genetic screen, and disease treatment. Molecular Therapy. (online) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2024.10.029.

- Pandelakis, M., Delgado, E. and Ebrahimkhani, M.R. (2020). CRISPR-Based Synthetic Transcription Factors In Vivo: The Future of Therapeutic Cellular Programming. Cell Systems, 10(1), pp.1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cels.2019.10.003.

About Sino Biological Inc.

Sino Biological is an international reagent supplier and service provider. The company specializes in recombinant protein production and antibody development. All of Sino Biological's products are independently developed and produced, including recombinant proteins, antibodies and cDNA clones. Sino Biological is the researchers' one-stop technical services shop for the advanced technology platforms they need to make advancements. In addition, Sino Biological offer pharmaceutical companies and biotechnology firms pre-clinical production technology services for hundreds of monoclonal antibody drug candidates.

Sino Biological's core business

Sino Biological is committed to providing high-quality recombinant protein and antibody reagents and to being a one-stop technical services shop for life science researchers around the world. All of our products are independently developed and produced. In addition, we offer pharmaceutical companies and biotechnology firms pre-clinical production technology services for hundreds of monoclonal antibody drug candidates. Our product quality control indicators meet rigorous requirements for clinical use samples. It takes only a few weeks for us to produce 1 to 30 grams of purified monoclonal antibody from gene sequencing.

Sponsored Content Policy: News-Medical.net publishes articles and related content that may be derived from sources where we have existing commercial relationships, provided such content adds value to the core editorial ethos of News-Medical.Net which is to educate and inform site visitors interested in medical research, science, medical devices and treatments.