Influenza is responsible for a substantial amount of global illness and death every year. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), in February 2025, there were 3–5 million severe cases and 290,000 to 650,000 respiratory deaths worldwide resulting from seasonal flu epidemics.1

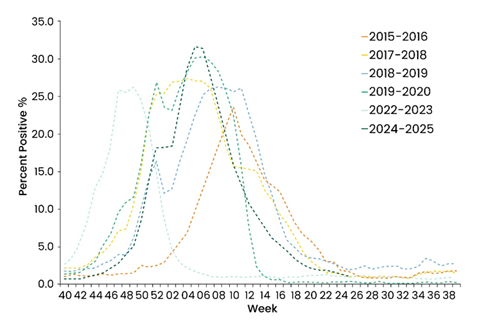

Following a temporary reduction during the COVID-19 pandemic, some regions have seen influenza cases rebound to pre-pandemic levels or higher (Figure 1).1,2

Older adults (≥65 years) and young children (≤4 years) continue to be at the highest risk of severe illness and hospitalization. People with weakened immunity and chronic conditions, pregnant women, fetuses, and people facing high exposure to influenza are also especially vulnerable.

These vulnerabilities underscore the importance of vaccination, and new solutions are continually required to address the ongoing influenza burden, challenges in vaccine development, and the need for comprehensive surveillance.3

Control efforts are further complicated by the virus’s capacity for rapid mutation, complex immune responses, and the need to utilize labor-intensive lab methods.

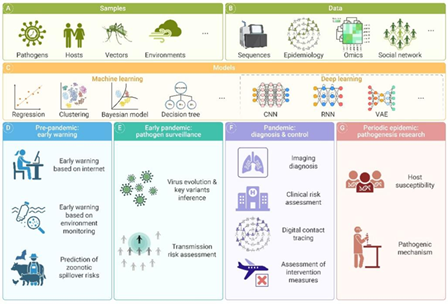

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) have the potential to transform influenza prevention and control, offering significant benefits in predicting viral changes, improving vaccine design, and enhancing manufacturing efficiency.

Figure 1. Weekly Rates of Laboratory-Confirmed Influenza Hospitalizations in US.2 Image Credit: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/whats-new/2025-2026-influenza-activity.html

AI and ML: A primer for vaccine development

AI, most notably its subfield of ML, involves the use of algorithms able to learn patterns and make predictions from large, complex datasets without the need for explicit programming for each scenario.

ML models used in vaccinology are trained on diverse data types, including viral genetic sequences, immunological assay results, protein structures, and clinical data.4

Using this data, these models can make high-dimensional predictions while identifying non-obvious, non-biased correlations.

Key applications of ML in influenza research include identifying immunogenic epitopes for novel vaccine designs, predicting antigenic drift from genetic data, forecasting host responses to infection or vaccination, and optimizing manufacturing processes.5,6,7

Figure 2. The schematic representation of AI utilization in infectious disease research.7 Image Credit: Hang-Yu Zhou et al.

AI-powered advances in influenza vaccine development

Informing strain selection and predicting antigenic evolution

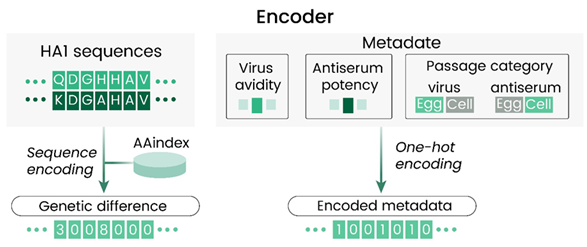

The selection of strains 6 to 9 months in advance of the season remains a key challenge in seasonal flu vaccine production. Machine learning (ML) bypasses labor-intensive hemagglutination inhibition (HI) assays, instead predicting antigenic properties from viral HA1 genetic sequences and metadata (Figure 3).

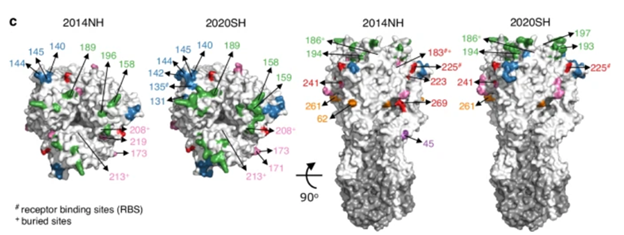

Quadeer and McKay have successfully developed models able to map genetic changes to antigenic variation. Their models can be used to inform vaccine strain selection by accurately identifying nine key antigenic sites in influenza's HA protein, predominantly in epitopes A, B, and D, with their relative importance changing over time (Figure 4).8

This approach allows public health authorities to make more cost-effective and faster support for vaccine strain decisions.

This method is also applicable to animal reservoirs with high antigenic diversity. Anderson and Zeller employed ML regression models that had been trained on HI assay data to predict antigenic distance based on certain genetic and amino acid mutations.

A random forest model was used to achieve strong accuracy and feature prioritization, highlighting amino acid identity in HA1 and mutations, particularly at position 145, as critical features for antigenic prediction.9

Figure 3. Details of the encoding performed at the input of the AdaBoost model with HA1 sequences of isolates in each virus.8 Image Credit: Syed Awais W. Shah et al.

Figure 4. Key HA sites that changed between the 2014NH and 2020SH seasons, color-coded by epitope. Epitopes A and D are shown in the top view (left), and epitopes C, E, and unlabeled sites in the front view (right).8 Image Credit: Syed Awais W. Shah et al.

Accelerating rational target selection and vaccine design

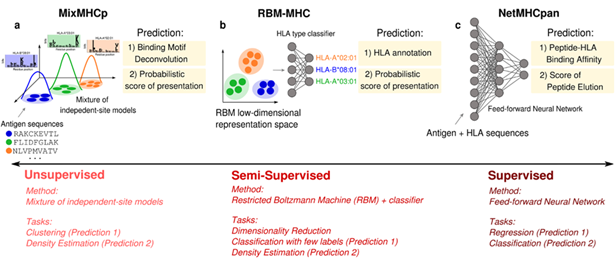

Machine learning (ML) is also extremely important beyond its role in strain selection, with ML driving the design of next-generation universal influenza vaccines. Bravi highlights that ML algorithms can be used to analyze vast libraries of viral protein sequences to predict B and T cell epitopes (recognition sites for the immune system) and identify correlates of protection.

ML models focus on either T-cell receptor (TCR) or antibody sequences to detect binding motifs. Alternatively, these models utilize paired TCR/antigen data to predict binding affinity and interactions (Figure 5).

Recent benchmarks show that the importance of model architecture is often outweighed by that of dataset quality and size, with performance AUROCs generally between 0.7 and 0.9.10

Figure 5. Examples of HLA class I antigen-presentation predictions generated by unsupervised, semi-supervised, and supervised models.10 Image Credit: Barbara Bravi.

Monitoring infection and immune responses

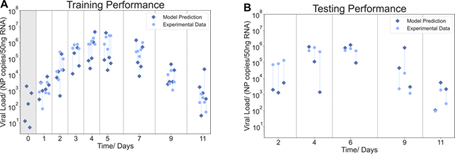

ML applications are also extending into the clinical realm, improving disease monitoring. Hernandez-Vargas E. and Jhutty S. conducted an investigation of supervised ML models’ capacity to predict key markers of lung infection, such as viral load, neutrophil counts, and cytokine levels. These predictions were made using only readily available hematological data obtained from blood samples.

ML applications have also been used to validate a feedforward neural network in mice that was able to accurately predict viral load trajectories, particularly during peak infection (Figure 6).11

Influenza infection has been shown to increase the risk of myocardial infarction, but the exact reason for this remains unclear.

Platelets play a role in immune regulation, support blood clotting, and have the potential to cause blood vessel blockages. Koupenova, Milka, et al. were able to build on previously developed models using differential equations and hematological markers, including lymphocyte, neutrophil, and platelet counts. These markers are known to support influenza diagnosis and pathogenesis understanding.12

The ongoing development of these types of ML tools is paving the way for enhanced disease tracking and the implementation of personalized medicine with non-invasive data.

Figure 6. Mapping of the lung viral load from blood data in the model training and testing.11 Image Credit: Suneet Singh Jhutty et al.

Sino Biological’s support for AI/ML-driven vaccine development

Sino Biological provides a range of products designed for AI-based vaccine research and the rapid development of diagnostics and vaccines, including antibodies, recombinant proteins, and cDNA clones.

The company’s recombinant antigens are widely utilized in the evaluation of immune responses to inactivated vaccines, the optimization of immunogen design, and the measurement of neutralizing antibody potency, which is essential in evaluating vaccine efficacy.

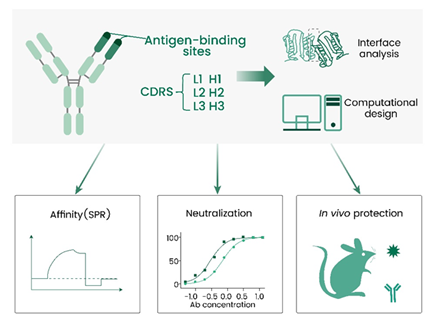

For example, Yang W. and Duan H. leveraged a structure-based computational design framework to optimize the broadly neutralizing antibody MEDI8852, which works by targeting the conserved stalk region of influenza A hemagglutinin (HA).

The resulting M18.1.2.2 variant showed improved affinity and neutralizing potency, inhibiting the proteolytic cleavage of the HA0 precursor (Sino Biological, 40715-V08H, 11706-V08H, 11689-V08H, 40239-V08B, 40174-V08B, 40359-V08B, 11711-V08H). It also delivers subsequent low-pH conformational changes in HA, offering enhanced inhibitory activity against multiple IAV subtypes versus the original antibody (Figure 7).13

Sumin and Sawan successfully integrated a Fiber Optic Biolayer Interferometry (FO-BLI) biosensor with machine learning regression models to predict future antibody responses.

The FO-BLI biosensor conducted fast affinity measurements of neutralizing (NAb) and binding (BAb) antibodies, employing key Sino Biologicals reagents, including various Spike Receptor-binding Domain (RBD) proteins (such as WT, BA.4/BA.5/BA.5.2, BA.4.6/BF.7, and XBB), biotinylated ACE2 Protein, and a Spike neutralizing antibody-rabbit Mab.14

Ciabattini A. and Pettini E. reported a machine learning strategy designed to identify Unaware SARS-CoV-2 Infected participants. Their work also enabled the identification of spike RBD (Sino Biological)-specific immune responses for long-term immune response of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine booster dose.15

Figure 7. A structure-based computational design framework to optimize a broadly neutralizing antibody targeting influenza A virus.13 Image Credit: doi.org/10.1016/j.str.2025.01.002

References and further reading

- World Health Organization (2025). Influenza (seasonal). (online) WHO. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/influenza-(seasonal).

- CDC (2025). Influenza Activity in the United States during the 2024–25 Season and Composition of the 2025–26 Influenza Vaccine. (online) Influenza (Flu). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/whats-new/2025-2026-influenza-activity.html.

- Clark, T.W., et al. (2024). Recent advances in the influenza virus vaccine landscape: a comprehensive overview of technologies and trials. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. DOI: 10.1128/cmr.00025-24. https://journals.asm.org/doi/full/10.1128/cmr.00025-24.

- Ong, E., et al. (2020). COVID-19 Coronavirus Vaccine Design Using Reverse Vaccinology and Machine Learning. Frontiers in Immunology, 11(1581). DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01581. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2020.01581/full.

- Lorbetskie, B., et al. (2025). Advancing Reversed-Phase Chromatography Analytics of Influenza Vaccines Using Machine Learning Approaches on a Diverse Range of Antigens and Formulations. Vaccines, (online) 13(8), p.820. DOI: 10.3390/vaccines13080820. https://www.mdpi.com/2076-393X/13/8/820.

- Alqaissi, E., et al. (2023). Novel graph-based machine-learning technique for viral infectious diseases: application to influenza and hepatitis diseases. Annals of medicine, (online) 55(2), p.2304108. DOI: 10.1080/07853890.2024.2304108. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/07853890.2024.2304108.

- Zhou, H.-Y., et al. (2024). Harnessing the power of artificial intelligence to combat infectious diseases: Progress, challenges, and future outlook. The Innovation Medicine, pp.100091–100091. DOI: 10.59717/j.xinn-med.2024.100091. https://the-innovation.org/article/doi/10.59717/j.xinn-med.2024.100091.

- Syed, Palomar, D.P., et al. (2024). Seasonal antigenic prediction of influenza A H3N2 using machine learning. Nature communications, 15(1). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-47862-9. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-024-47862-9.

- Zeller, M.A., et al. (2021). Machine Learning Prediction and Experimental Validation of Antigenic Drift in H3 Influenza A Viruses in Swine. mSphere, 6(2). DOI: 10.1128/msphere.00920-20. https://journals.asm.org/doi/full/10.1128/msphere.00920-20.

- Bravi, B. (2024). Development and use of machine learning algorithms in vaccine target selection. npj Vaccines, (online) 9(1). DOI: 10.1038/s41541-023-00795-8. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41541-023-00795-8.

- Suneet Singh Jhutty, et al. (2022). Predicting Influenza A Virus Infection in the Lung from Hematological Data with Machine Learning. mSystems, 7(6). DOI: 10.1128/msystems.00459-22. https://journals.asm.org/doi/full/10.1128/msystems.00459-22.

- Koupenova, M., et al. (2019). The role of platelets in mediating a response to human influenza infection. Nature Communications, (online) 10(1), p.1780. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-019-09607-x. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-019-09607-x.

- Duan, H., et al. (2025). Computational design and improvement of a broad influenza virus HA stem targeting antibody. Structure, (online) 33(3), pp.489-503.e5. DOI: 10.1016/j.str.2025.01.002. https://www.cell.com/structure/abstract/S0969-2126(25)00002-4.

- Bian, S., et al. (2024). Dynamic Profiling and Prediction of Antibody Response to SARS-CoV-2 Booster-Inactivated Vaccines by Microsample-Driven Biosensor and Machine Learning. Vaccines, (online) 12(4), pp.352–352. DOI: 10.3390/vaccines12040352. https://www.mdpi.com/2076-393X/12/4/352.

- Montesi, G., et al. (2025). Machine learning approaches to dissect hybrid and vaccine-induced immunity. Communications Medicine, (online) 5(1). DOI: 10.1038/s43856-025-00987-4. https://www.nature.com/articles/s43856-025-00987-4.

Acknowledgments

Produced from materials originally authored by Sino Biological.

About Sino Biological Inc.

Sino Biological is an international reagent supplier and service provider. The company specializes in recombinant protein production and antibody development. All of Sino Biological's products are independently developed and produced, including recombinant proteins, antibodies and cDNA clones. Sino Biological is the researchers' one-stop technical services shop for the advanced technology platforms they need to make advancements. In addition, Sino Biological offers pharmaceutical companies and biotechnology firms pre-clinical production technology services for hundreds of monoclonal antibody drug candidates.

Sino Biological's core business

Sino Biological is committed to providing high-quality recombinant protein and antibody reagents and to being a one-stop technical services shop for life science researchers around the world. All of our products are independently developed and produced. In addition, we offer pharmaceutical companies and biotechnology firms pre-clinical production technology services for hundreds of monoclonal antibody drug candidates. Our product quality control indicators meet rigorous requirements for clinical use samples. It takes only a few weeks for us to produce 1 to 30 grams of purified monoclonal antibody from gene sequencing.

Sponsored Content Policy: News-Medical.net publishes articles and related content that may be derived from sources where we have existing commercial relationships, provided such content adds value to the core editorial ethos of News-Medical.Net which is to educate and inform site visitors interested in medical research, science, medical devices and treatments.